Most people think pharmacies make money because they sell expensive brand-name drugs. But the truth is, generics are what keep most pharmacies open. It’s not about the price tag-it’s about the math behind the markup.

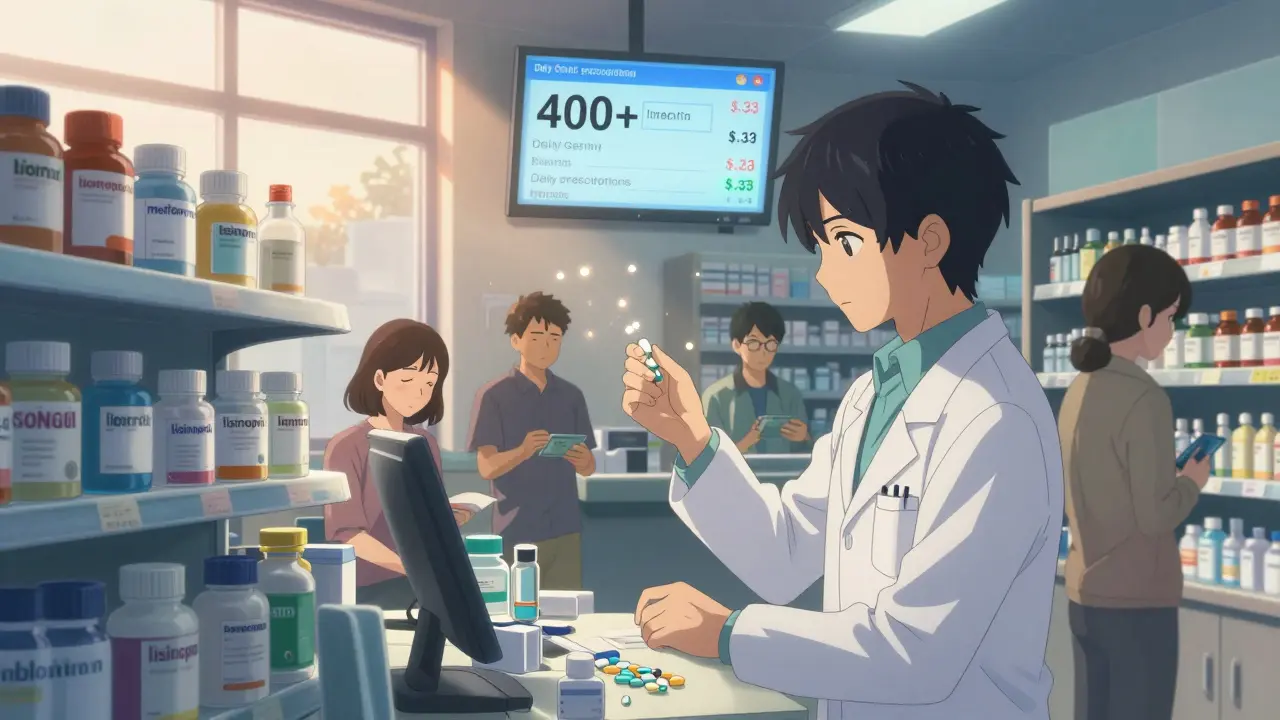

Picture this: a customer walks in for a 30-day supply of metformin, a common diabetes medication. The brand version might cost $150. The generic? $12. The pharmacy gets reimbursed $15 for the generic. That’s a $3 gross profit. Sounds tiny, right? But that same pharmacy fills 400 generic prescriptions a day. Now you’re talking $1,200 in gross profit just from metformin alone. Multiply that across dozens of other generics-ibuprofen, lisinopril, levothyroxine-and you’ve got the real engine of pharmacy revenue.

Why Generics Are the Profit Engine

Generics make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. But they only account for about 25% of total drug spending. That’s because brand-name drugs cost ten, sometimes a hundred times more. Yet, pharmacies make nearly 12 times more profit per prescription on generics than on brand-name drugs. How?

The answer lies in the markup structure. Generic manufacturers sell drugs at low wholesale prices-sometimes just pennies per pill. Pharmacies mark them up by 40-45%. That’s not greed. It’s survival. Brand-name drugs, by contrast, have list prices inflated by patents and marketing. Pharmacies get reimbursed based on those high prices, but their markup is only 3-5%. So even though a brand drug might bring in $100 in revenue, the pharmacy walks away with maybe $3. A generic that brings in $15? The pharmacy keeps $6-$7.

It’s a paradox: the cheapest drugs are the most profitable. And without them, most community pharmacies would lose money on every transaction.

Who Really Controls the Money?

Pharmacies don’t set their own prices. Pharmacy Benefit Managers-PBMs like CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx-do. These middlemen negotiate rebates and reimbursement rates with drug manufacturers and pharmacies. They’re the hidden players in this game.

PBMs use something called “spread pricing.” They tell the health plan the drug costs $20. They tell the pharmacy they’ll pay $15. The $5 difference? That’s the PBM’s profit. And it’s not always disclosed. Independent pharmacies often don’t know how much they’re being underpaid until they get a clawback notice weeks later-suddenly, they owe the PBM money because the reimbursement rate was adjusted retroactively.

Some PBMs also require pharmacies to accept “non-negotiable” contracts. If you want to be in-network with a major insurer, you have to agree to their reimbursement terms. No room for discussion. That’s why many independent pharmacies are losing money on every generic they dispense-even if the gross margin looks good on paper.

The Collapse of Independent Pharmacies

Five years ago, many independent pharmacies made 8-10% net profit on generics. Today, it’s closer to 2%. Overhead hasn’t dropped. Rent, staff wages, compliance costs, and insurance premiums have all gone up. Meanwhile, reimbursement rates have flatlined or dropped.

The National Community Pharmacists Association found that 68% of independent pharmacy owners list declining generic reimbursement as their biggest threat. Between 2018 and 2023, 3,000 independent pharmacies shut down. That’s nearly one every day.

Why? Because PBMs and large chains have the power to squeeze them out. Chain pharmacies like Walgreens and CVS have their own PBMs. They can shift profits internally. Independent pharmacies can’t. They’re stuck taking whatever the PBM gives them.

And it’s getting worse. More generic drugs are being made by just one manufacturer-no competition means no price pressure. In some cases, a single-source generic costs more than the brand-name version. Pharmacies are forced to dispense it anyway, because the patient’s insurance won’t cover the brand. So they lose money on a drug they’re legally required to fill.

How Some Pharmacies Are Fighting Back

Not all pharmacies are going under. Some are adapting.

One strategy? Bypass PBMs entirely. Some pharmacies now offer direct cash pricing for generics. Instead of billing insurance, they charge $5 for a 30-day supply of lisinopril. It’s transparent. No spreads. No clawbacks. Customers pay out of pocket, and the pharmacy keeps the full $5. Amazon Pharmacy and Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company have made this model popular. Cost Plus charges $20 for the drug plus a $3 dispensing fee. That’s it. No hidden fees. No middleman.

Another tactic? Move into services. Medication Therapy Management (MTM) lets pharmacists spend time with patients-reviewing all their drugs, checking for interactions, helping with adherence. Medicare pays for these services. A well-run MTM program can add $10,000-$20,000 a month in revenue, with higher margins than dispensing pills.

Some pharmacies are also becoming specialty pharmacies. They handle complex, high-cost drugs for conditions like multiple sclerosis or cancer. These drugs come with higher reimbursement rates and built-in support services. The profit isn’t in the pill-it’s in the care.

The Bigger Picture: Who Pays the Price?

When pharmacies struggle, patients pay. More people skip doses because they can’t afford co-pays. Others switch to cheaper, less effective drugs. The system is designed so that the cheapest drug is the most profitable-but only if the pharmacy can get paid fairly.

Right now, over 60% of what Americans spend on prescriptions goes to middlemen-not manufacturers, not pharmacies, not patients. That’s the real scandal. The drug cost is $10. The patient pays $15. The pharmacy gets $12. The PBM keeps $3. Who’s getting rich? Not the people who fill the prescription. Not the people who make it.

States are starting to act. California, Texas, and Illinois passed laws in 2022-2023 requiring PBMs to disclose how they calculate reimbursement. The Federal Trade Commission is investigating PBM practices. The Inflation Reduction Act, starting in 2026, will let Medicare negotiate drug prices. That could lower overall spending-but it might also squeeze generic margins even more.

What’s Next for Pharmacy Economics?

The future of pharmacy profit isn’t in selling more pills. It’s in adding value. Pharmacies that become health hubs-offering vaccinations, chronic disease coaching, point-of-care testing-will survive. Those that just count pills? They’ll disappear.

Independent pharmacies aren’t dead yet. But they need to stop playing by the old rules. They need to demand transparency. They need to build direct relationships with patients. They need to stop relying on PBM reimbursements that are designed to fail them.

Generics will always be the backbone of pharmacy revenue. But if the system doesn’t change, the people who dispense them won’t be around to do it.

Why do pharmacies make more profit on cheap generics than expensive brand-name drugs?

Generics cost very little to produce and are sold at low wholesale prices. Pharmacies mark them up by 40-45%, which means even a $10 drug can generate $4-$5 in gross profit. Brand-name drugs have high list prices, but pharmacies are reimbursed based on those inflated prices and only get a 3-5% markup. So while a brand drug might bring in $100, the pharmacy only keeps $3-$5. A generic that brings in $15 can earn $6-$7. Volume and markup combine to make generics the real profit driver.

What role do Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) play in pharmacy profits?

PBMs act as middlemen between pharmacies, drug manufacturers, and insurers. They set reimbursement rates and use practices like spread pricing-charging insurers more than they pay pharmacies-and clawbacks-demanding money back after payment. This squeezes pharmacy margins, especially for independents who can’t negotiate better terms. PBMs keep the difference as profit, often without transparency. The top three PBMs control 80% of the market, giving them enormous leverage.

Why are independent pharmacies closing faster than chain pharmacies?

Chain pharmacies often own their own PBMs or have exclusive contracts with them, allowing them to shift profits internally. Independent pharmacies rely on third-party PBMs that set unfair reimbursement rates. They also face higher overhead per prescription due to lower volume. Between 2018 and 2023, 3,000 independent pharmacies shut down. Without reform, another 20-25% could close by 2027.

Can pharmacies make money without relying on insurance reimbursements?

Yes. Some pharmacies now offer direct cash pricing for generics-charging $5 for a 30-day supply of common medications. This cuts out PBMs entirely. Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company and Amazon Pharmacy use this model successfully. Pharmacies also earn more by offering services like Medication Therapy Management, vaccinations, or chronic care coaching, which are reimbursed separately by Medicare or employers.

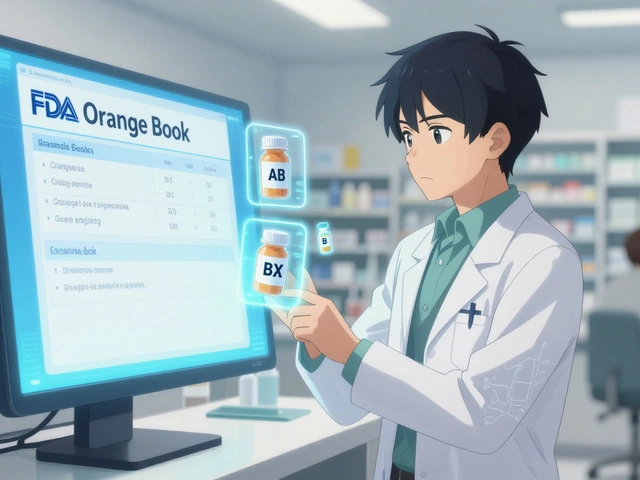

Are generic drug prices going to keep falling?

Not necessarily. While competition used to drive prices down, consolidation in generic manufacturing has reduced it. The top five manufacturers now control 45% of the market. Some generics are made by only one company, eliminating price competition. In rare cases, single-source generics cost more than the brand-name version. The FDA has approved thousands of new generics, but market power is now the bigger barrier to lower prices.

Jessica Salgado

December 15, 2025 AT 14:16So let me get this straight-we’re paying $15 for a pill that costs $0.10 to make, and the pharmacy barely makes a buck on it? Meanwhile, the PBM pockets $5 in the dark and calls it a ‘service fee’? This isn’t capitalism-it’s a rigged casino where the house always wins, and the pharmacist is the guy cleaning up the chips after everyone’s lost.

I’ve seen my grandma skip her lisinopril because her co-pay jumped from $5 to $12. She’s not lazy. She’s just trying to survive. And the system? It’s designed to make her feel guilty for it.

Salome Perez

December 16, 2025 AT 00:21One cannot help but marvel at the elegant, albeit tragic, irony embedded within the contemporary pharmaceutical distribution paradigm. The very agents entrusted with the stewardship of public health-pharmacists-are now reduced to statistical artifacts in a ledger dominated by opaque corporate intermediaries. The generative logic of profit, once rooted in service, has been sublimated into a mechanical arithmetic of volume and leverage.

It is not merely a matter of reimbursement rates; it is the erosion of professional dignity. When a pharmacist’s expertise is valued less than a spreadsheet’s algorithm, we have not merely broken a business model-we have broken a covenant.

Kent Peterson

December 16, 2025 AT 21:15Josh Potter

December 18, 2025 AT 11:39Evelyn Vélez Mejía

December 20, 2025 AT 05:24The structural dissonance between moral imperative and economic reality in pharmaceutical dispensing is nothing short of a societal pathology. The profit model predicated on volume of low-margin goods is inherently unstable when externalized costs-regulatory compliance, labor inflation, and infrastructure maintenance-are not proportionally reimbursed.

Furthermore, the consolidation of Pharmacy Benefit Managers into a triopoly represents not merely market inefficiency, but a monopolistic capture of the public health infrastructure. The absence of transparency in spread pricing constitutes a breach of fiduciary duty, and the retroactive clawbacks are, legally and ethically, indefensible.

It is not the pharmacist’s failure-it is the failure of governance. The state must intervene to cap PBM margins, mandate disclosure, and establish a public reimbursement floor for generics. Otherwise, the pharmacy as a community institution will vanish, replaced by algorithmic kiosks in Walmart.

Victoria Rogers

December 21, 2025 AT 05:01Jane Wei

December 22, 2025 AT 23:17Nishant Desae

December 22, 2025 AT 23:44As someone from India, where generic drugs are the lifeline for millions, I see this story with deep emotion. In my country, a 30-day supply of metformin costs less than a dollar. But here, even though the pill is the same, the system turns it into a bureaucratic nightmare. The real tragedy is not the profit margin-it’s the human cost. People skipping doses. Elders choosing between food and medicine. The pharmacist, who knows your name, your kids, your fears-now forced to choose between staying open or staying honest.

When I visited a small pharmacy in Texas last year, the owner told me, ‘We don’t sell pills. We sell peace of mind.’ That’s what we’re losing. Not money. Soul.

Meghan O'Shaughnessy

December 23, 2025 AT 20:08I’ve been a pharmacist for 22 years. I’ve seen this shift from community care to corporate logistics. The most heartbreaking moment? When a teenager came in for her first asthma inhaler. She didn’t have insurance. I gave her the generic for $12 cash. She asked if I could ‘just give it to her.’ I said no. But I gave her an extra spacer and wrote down how to use it. She cried. I cried.

Pharmacies aren’t just stores. We’re the last place people feel seen. If we disappear, who will explain side effects? Who will notice when someone’s depression is worsening? Who will be there when the system forgets them?

Kaylee Esdale

December 25, 2025 AT 03:26