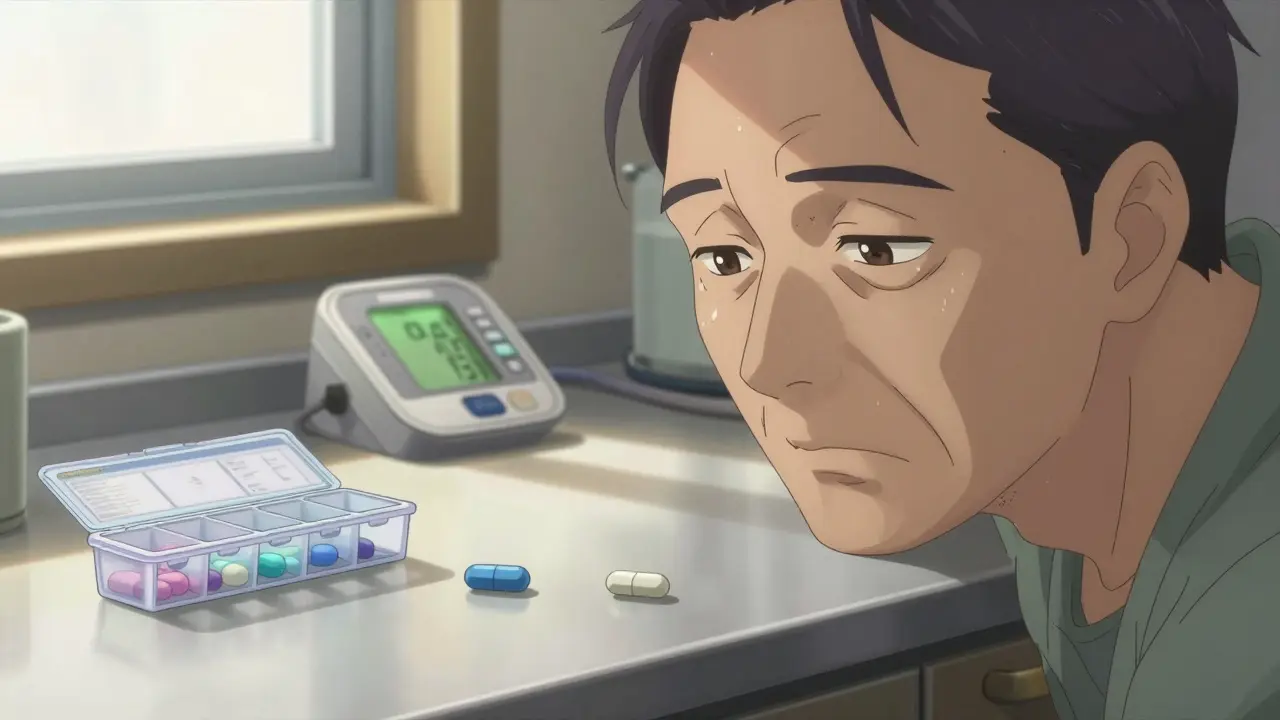

Imagine you’re managing high blood pressure. Your doctor used to give you one pill a day that combined two medicines. Now, you’re handed two separate pills - one blue, one white - and told to take them together. It’s cheaper, they say. But you forget which is which. You miss a dose. Your blood pressure spikes. This isn’t rare. It’s happening to thousands of patients every day, not because it’s better, but because it’s easier for doctors to write and pharmacies to fill. This is the reality of de facto combinations: when patients take multiple generic pills instead of a single fixed-dose combination (FDC) that contains the same drugs in one tablet.

What Exactly Is a De Facto Combination?

A de facto combination isn’t a drug approved by regulators. It’s a practice. It happens when a doctor prescribes two or more separate generic medications - like amlodipine and valsartan - instead of a single FDC pill that already contains them together. The combination works clinically, but it wasn’t tested as a unit. No one studied how these two specific generics interact in the body when taken together. No stability tests. No bioequivalence checks. Just two pills, side by side, in the same bottle.

The European Medicines Agency defines FDCs as products with two or more active ingredients in a fixed ratio, in one dosage form. These go through rigorous review to prove that the combination is safe, effective, and better than taking the drugs separately. De facto combinations skip all that. They’re legal - but they’re not regulated as a combination. They’re just two separate drugs, prescribed together.

Why Do Doctors Prescribe Separate Generics?

There are three big reasons: cost, flexibility, and habit.

Cost is the most common driver. In some markets, especially where generic competition is fierce, buying two separate generic pills can be cheaper than a branded FDC. In India, for example, a 2012 parliamentary report found that many FDCs offered no real advantage over individual drugs - and sometimes, the separate generics cost less. In the U.S., a patient might save $10-$15 a month by switching from a branded FDC to generic amlodipine and lisinopril. For someone on a fixed income, that matters.

Flexibility is the clinical argument. Not every patient needs the exact dose in an FDC. Say your FDC has 10 mg of amlodipine and 160 mg of valsartan. But your body responds better to 5 mg of amlodipine and 160 mg of valsartan. The FDC doesn’t offer that. So your doctor prescribes the two separately. This is especially common in patients with kidney disease, older adults, or those on multiple medications where small dose changes make a big difference.

And then there’s habit. Many doctors were trained before FDCs became common. They’re used to prescribing individual drugs. They don’t always know what FDCs are available, or whether they’re covered by insurance. Sometimes, they just write what’s familiar.

The Hidden Risks of Taking Separate Pills

De facto combinations sound harmless. But they come with serious downsides.

First, adherence drops. Every extra pill you have to take reduces your chance of sticking to the regimen. A study published in PubMed found that each additional pill per day cuts adherence by about 16%. Patients on FDCs are 22% more likely to take their meds consistently than those on separate generics. That’s not a small gap. It’s the difference between controlled blood pressure and a stroke.

Second, there’s no safety net. When a company makes an FDC, they have to prove the combination is safe. They test for drug interactions, how the ingredients affect each other’s absorption, and whether the combination causes unexpected side effects. With de facto combinations, none of that happens. Two generics that are perfectly safe on their own might behave differently when taken together. The FDA found in 2020 that 12.7% of generic drugs have bioavailability differences compared to their reference products. That means one generic amlodipine might release slower than another - and if you’re mixing brands, you’re playing with fire.

Third, errors happen. Patients mix up pills. Pharmacists misfill bottles. Electronic health records get confused. A 2022 CMS report showed that regimens using separate generics generated 28% more documentation errors than FDCs. One patient on Reddit wrote: “I switched from a single Amlodipine/Benazepril pill to two generics to save $15 a month. I missed two doses because I forgot which blue pill was which.”

When Are De Facto Combinations Actually Useful?

They’re not always wrong. There are real cases where they make sense.

Take diabetes. A patient with type 2 diabetes and kidney impairment might need 500 mg of metformin and 25 mg of sitagliptin. But the only FDC available is 1000 mg metformin and 50 mg sitagliptin - too much for their kidneys. Prescribing separate generics lets the doctor fine-tune the dose. One patient on Drugs.com reported keeping their A1c at 6.2% for 18 months using this approach.

Same with HIV. Some regimens require dose adjustments based on weight, liver function, or drug interactions. FDCs are common in HIV treatment - 89% of patients use them - but when adjustments are needed, doctors go back to separate generics. The key is intentionality. It’s not a cost-saving shortcut. It’s a clinical decision.

And it’s not just about dosing. Some patients have allergies to inactive ingredients in FDCs - like dyes or fillers. If the only FDC contains a dye they react to, separate generics might be the only safe option.

What’s the Healthcare System Doing About It?

Not enough - but things are changing.

The FDA issued a safety warning in January 2023 about “unintended consequences of untested drug combinations,” citing 147 adverse events potentially linked to de facto combinations. The EMA launched a 2023-2025 project to study off-label combinations. In the U.S., the American Pharmacists Association found that 72% of pharmacists are worried about medication errors with separate generics.

Some solutions are emerging. PillPack by Amazon started a Combination Therapy Support Program in 2021 that pre-sorts pills into daily packets with color-coded labels. They reported a 41% drop in adherence issues. Hospitals are training prescribers to recognize when FDCs are appropriate. A 2021 study showed physicians who got this training were 37% less likely to prescribe inappropriate de facto combinations.

Technology is helping too. New electronic prescribing systems are starting to flag when a doctor writes two separate generics that are already available as an FDC. They’ll suggest: “Amlodipine 5 mg + Valsartan 160 mg is available as a single pill. Consider switching.”

What Should Patients Do?

If you’re on separate generics for a condition that has an FDC option, ask these questions:

- Is there a fixed-dose combination that contains the same drugs at the same doses I’m taking?

- Am I taking this because it’s cheaper, or because it’s better for me?

- Do I ever mix up which pill is which?

- Have I missed doses in the last month?

If the answer to any of those is yes, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. Ask if an FDC is an option. If cost is the issue, ask if a generic FDC exists - many do now. In the U.S., generic FDCs for hypertension and diabetes are widely available and often cost the same as two separate generics.

Don’t assume separate pills are safer or smarter. Sometimes, they’re just more complicated.

The Future: More FDCs, Better Support

The trend is shifting. Companies are developing modular FDCs - pills that let you adjust doses without splitting pills. AstraZeneca filed a patent in 2022 for a combination pill that lets you remove a small insert to reduce one component’s dose. That’s the future: the convenience of a single pill, with the flexibility of customization.

Meanwhile, regulatory agencies are cracking down on untested combinations. By 2035, analysts predict that unmonitored de facto combinations will drop by 60% thanks to smarter e-prescribing and better patient support.

But until then, the choice isn’t always clear. For some, separate generics are a lifeline. For others, they’re a silent risk. The key is awareness - and asking the right questions.

Are de facto combinations illegal?

No, they’re not illegal. Doctors can legally prescribe any approved generic drug, even if they’re combining them in ways that aren’t FDA-approved as a single product. But while it’s legal, it’s not always safe or recommended. Regulators are increasingly concerned about the lack of testing and higher risk of errors.

Can I switch from separate generics to an FDC on my own?

No. Never change your medication regimen without talking to your doctor or pharmacist. Even if the drugs are the same, the dosages, release profiles, or inactive ingredients might differ. Switching without guidance could lead to under- or over-treatment, or unexpected side effects.

Why don’t all FDCs come in generic form?

Some FDCs are still under patent protection. Others aren’t made as generics because manufacturers don’t see enough demand, or the combination is too complex to produce reliably. But many common FDCs - like those for high blood pressure and diabetes - now have affordable generic versions. Ask your pharmacist if a generic FDC exists for your regimen.

Do de facto combinations cost more overall?

Not always. While two separate generics might seem cheaper at the pharmacy counter, the real cost includes missed doses, ER visits, and hospitalizations from poor adherence. A 2022 study in Health Affairs found that patients on separate generics had 30% higher healthcare costs over a year due to complications from non-adherence. The upfront savings can be misleading.

How can I make de facto combinations safer?

Use a pill organizer with clear labels. Ask your pharmacist to color-code your pills. Set phone reminders for each dose. Request a written schedule with pictures of each pill. Some pharmacies offer blister packs with daily doses pre-sorted. These small steps can cut your risk of error by half.

Cara C

December 21, 2025 AT 22:26I used to take two separate pills for my BP until my pharmacist showed me the generic FDC was the same price. I switched and haven’t missed a dose since. Seriously, if you’re juggling colors and sizes, just ask. It’s not that hard.

Jay lawch

December 22, 2025 AT 22:47This whole thing is a corporate scam. Big Pharma doesn’t want you taking cheap generics because they can’t control the market. They push FDCs because they’re easier to patent, even when the science doesn’t justify it. In India, we’ve been using separate generics for decades-no one dies. The FDA is just another arm of Wall Street. They don’t care about patients, only profits. The real problem? Doctors are paid to prescribe what the reps tell them to. Wake up.

Christina Weber

December 23, 2025 AT 00:24There’s a fundamental misunderstanding here. De facto combinations aren’t ‘untested’-each individual component has undergone rigorous FDA approval. The issue isn’t safety, it’s adherence. And while it’s true that pill burden reduces compliance, conflating that with ‘hidden risks’ is misleading. Bioavailability differences between generics are statistically negligible in clinical practice. The real danger is overmedicalizing a simple behavioral issue.

Theo Newbold

December 23, 2025 AT 13:14Let’s run the numbers. 22% higher adherence with FDCs? That’s meaningless without context. If 80% of patients on separate pills are still adherent, that’s 4 out of 5 people. Meanwhile, the cost differential? In rural America, $15/month is a meal. The system rewards complexity because it’s profitable. The real villain isn’t the patient forgetting a pill-it’s a healthcare economy that treats compliance as a moral failing instead of a design flaw.

Michael Ochieng

December 23, 2025 AT 18:35As someone who grew up in Kenya and now lives in Ohio, I’ve seen both sides. In Nairobi, we took separate pills because that’s all we could afford. Here, I was shocked when my pharmacist said I could get a combo pill for the same price. It’s not about being ‘better’-it’s about access. The system needs to stop assuming everyone has the same resources. Maybe the answer isn’t forcing everyone into FDCs, but making sure the cheapest option is also the easiest one.

Erika Putri Aldana

December 24, 2025 AT 14:39Ugh. Why is this even a thing? Just give me one pill. I can’t even remember to take my vitamins, let alone keep track of blue vs white. This is why people end up in the ER. Someone needs to fix this.

Jerry Peterson

December 26, 2025 AT 10:04My grandma takes five pills a day. She uses a pill organizer with pictures on it. That’s the real solution-not switching to FDCs, but helping people manage what they’ve got. Doctors should be asking: ‘What’s your daily life like?’ not just ‘Which pill do you prefer?’

Adrian Thompson

December 28, 2025 AT 06:32Oh great. Another ‘patient education’ lecture. Meanwhile, the same companies pushing FDCs are the ones lobbying against generic price caps. You think they care if you mix up pills? They care if you buy their branded version. The system is rigged. FDCs aren’t safer-they’re just more profitable. And don’t get me started on how pharmacies get kickbacks for pushing combos. Wake up, sheeple.

Jon Paramore

December 29, 2025 AT 06:50De facto combos are clinically valid when dose titration is needed. But in 70% of hypertension cases, the FDC dose is appropriate. The real issue is prescriber awareness. A 2021 JAMA study showed 68% of PCPs couldn’t name a single generic FDC for ACE/ARB+CCB. That’s not patient error-that’s system failure. EHR alerts help, but only if they’re not buried in 12 pop-ups.

Ben Warren

December 30, 2025 AT 02:30It is an undeniable and regrettable fact that the current paradigm of prescribing separate generic medications, colloquially referred to as de facto combinations, constitutes a suboptimal therapeutic strategy that is fundamentally at odds with the principles of evidence-based pharmacotherapy. The absence of standardized bioequivalence validation, coupled with the documented increase in medication error rates and the statistically significant reduction in patient adherence, renders this practice not merely inconvenient, but ethically and clinically indefensible. The regulatory lacuna permitting such practices reflects a systemic failure of oversight that demands immediate institutional intervention, including mandatory EHR prompts, prescriber continuing education mandates, and the elimination of financial incentives favoring fragmented regimens.

Teya Derksen Friesen

December 31, 2025 AT 06:16I’m a pharmacist in Vancouver. We started offering free blister packs for multi-pill regimens last year. Adherence jumped 50% in six months. No one had to switch pills. No one had to pay more. We just made it easier. Sometimes the answer isn’t changing the drug-it’s changing the delivery.