When you pick up a prescription, you might not realize that the pill in your hand could be different from what your doctor wrote on the script. That’s because of pharmacy substitution laws-rules that let pharmacists swap out brand-name drugs for cheaper generics or biosimilars. These laws exist in every U.S. state and Washington, D.C., but they’re not the same anywhere you go. What’s allowed in California might be banned in Oklahoma. What’s automatic in Texas might need your signature in New York. If you’re on a medication with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, phenytoin, or levothyroxine-this isn’t just a paperwork issue. It’s a safety issue.

What Exactly Is Pharmacy Substitution?

Pharmacy substitution means a pharmacist gives you a different drug than what’s on the prescription, but one that’s considered therapeutically equivalent. For small-molecule drugs (like antibiotics or blood pressure pills), this usually means switching from a brand-name drug like Lipitor to its generic version, atorvastatin. For biologics (like Humira or Enbrel), it means switching to a biosimilar-a highly similar, but not identical, version of the original biologic. The FDA says generics are just as safe and effective as brand-name drugs. They have to prove they deliver the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same rate. That’s why generics cost 80-85% less. But not all drugs are created equal. Some medications have what’s called a narrow therapeutic index (NTI). That means the difference between a dose that works and one that causes harm is tiny. Even small changes in how the drug is absorbed can lead to serious side effects. That’s why some states block substitution for these drugs entirely.State Laws Fall Into Three Categories

Not every state treats substitution the same way. The rules come down to three main types:- Mandatory substitution (19 states + DC): The pharmacist must substitute unless the prescriber says "dispense as written." States like California, New York, and Texas use this model. The goal is to maximize savings.

- Permissive substitution (31 states + DC): The pharmacist can substitute, but doesn’t have to. They might choose not to if they’re unsure about equivalence or if the patient has had issues before. Most states fall into this group.

- Restrictive substitution (no state is fully restrictive, but many have partial bans): Some states ban substitution for specific drugs, especially NTI drugs. For example, Hawaii won’t allow substitution for antiepileptic drugs without both the prescriber’s and patient’s consent. Kentucky keeps a list of drugs that can’t be swapped out at all.

Do You Need to Give Consent?

This is where things get messy. In 7 states plus DC, pharmacists must get your written or verbal consent before swapping your drug. In 31 states plus DC, they only have to notify you after the fact-usually by putting a sticker on the bottle or telling you at the counter. And in 19 states? No notification at all. You might not even know you got a different drug until you see the receipt or your insurance statement. That’s a problem. If you’re on a complex regimen-say, taking five different medications for diabetes, heart disease, and depression-switching one without telling you could throw off your whole system. A 2009 study found that states requiring patient consent had 25% lower generic substitution rates. That doesn’t mean consent is bad. It means people are more cautious when they’re involved in the decision.

What About Biosimilars?

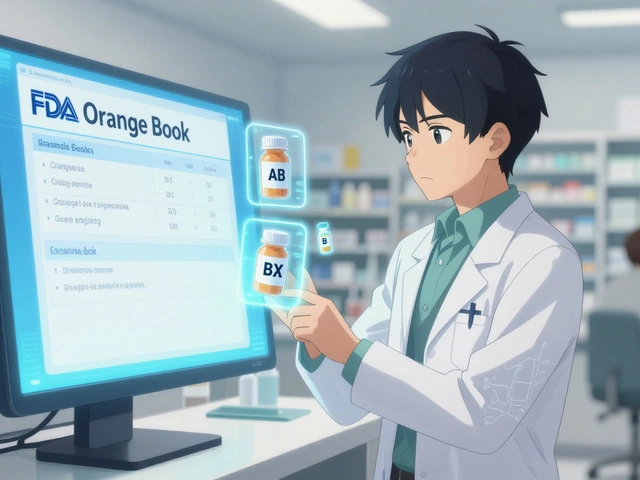

Biosimilars are trickier. Unlike generics, they’re not exact copies. They’re made from living cells, so tiny differences in manufacturing can affect how they work. The FDA only calls a biosimilar “interchangeable” if it can be swapped without any risk to safety or effectiveness. As of late 2023, only 10 out of 38 approved biosimilars have that designation. Most states treat interchangeable biosimilars differently than generics. In 45 states, pharmacists must notify the prescriber after substitution. In 12 states, they need the prescriber’s permission first. In 15 states, they can’t substitute at all if the biosimilar costs more than the original-even if your insurance covers it. Florida, Georgia, and Illinois require notification to both patient and doctor within 24-72 hours. Alabama and Mississippi? They barely require anything beyond a note in the pharmacy file.What Can You Do as a Patient?

You have rights-even if your pharmacist doesn’t always remind you of them.- Ask if substitution happened. If you notice a change in pill color, shape, or size, ask. You’re entitled to know.

- Refuse substitution. You can say no, even in states with mandatory substitution. Just say, “I’d like the brand as prescribed.”

- Check your prescription. Your doctor can write “dispense as written” or “do not substitute” on the script. That overrides any state law. In 18 states, though, the doctor must explain why they’re blocking substitution.

- Review your pharmacy records. By law, 42 states require pharmacists to keep records of substitutions for at least two years. You can request them.

What Can Pharmacists Do?

Pharmacists are on the front lines. They have to juggle state laws, insurance rules, and patient safety-all while managing long lines and busy hours.- Know your state’s rules. Every state board of pharmacy has a website with current substitution laws. Bookmark it.

- Use the FDA’s Purple Book. It lists which biosimilars are interchangeable. Don’t rely on labels alone.

- Document everything. If you substitute, write down the product name, lot number, and date. In 42 states, that’s required.

- Communicate clearly. Even if your state doesn’t require it, tell patients: “This is a generic version of your medication. It’s the same active ingredient, just cheaper.”

Why Do These Laws Vary So Much?

There’s no national standard because drug substitution is seen as a state-level issue. Some states prioritize cost savings. Others prioritize control. The pharmaceutical industry lobbies hard in both directions-brand-name companies want to block substitution; generic manufacturers want to expand it. The result? A patchwork of rules. A patient who moves from New York to Texas might find their medication switched without warning. A pharmacist who works in multiple states might get fined for following the wrong rule.What’s Changing in 2026?

New laws are popping up. California strengthened its biosimilar notification rules in 2023. New York expanded substitution authority for certain biosimilars. The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy is pushing a model law that 22 states have already started adopting. It standardizes notification timelines and documentation. The goal? Reduce confusion. But until then, you can’t assume anything. What’s true today in one state might be false tomorrow in the next.Key Takeaways

- All 50 states and DC have laws allowing pharmacy substitution, but they vary widely.

- Generics save 80-85% on drug costs-$313 billion annually in the U.S.

- 19 states require substitution; 31 allow it optionally.

- 7 states require your consent before substitution; 19 don’t even notify you.

- Biosimilars have stricter rules: 45 states require prescriber notification.

- You can always refuse substitution, even if the law allows it.

- Prescribers can block substitution by writing “dispense as written”-but 18 states require a reason.

- Always check your medication when you pick it up. If it looks different, ask.

Can a pharmacist substitute my brand-name drug without telling me?

Yes, in 19 states, pharmacists are not required to notify you before substituting a generic drug. In those states, you might only find out when you see the label on your bottle or your insurance statement. However, in 7 states plus Washington, D.C., explicit consent is required before substitution. Always ask if you’re unsure.

Are generic drugs as safe as brand-name drugs?

For most medications, yes. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand. They must also prove they work the same way in your body. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, levothyroxine, or phenytoin-even small differences can cause problems. That’s why some states ban substitution for these.

What’s the difference between a biosimilar and a generic?

Generics are chemically identical copies of small-molecule drugs. Biosimilars are highly similar to biologic drugs (made from living cells), but not exact copies. Because of their complexity, biosimilars can have minor differences in structure or function. Only 10 out of 38 approved biosimilars in the U.S. have been labeled “interchangeable” by the FDA-meaning they can be substituted like generics. The rest require prescriber approval.

Can my doctor stop substitution from happening?

Yes. In every state, a prescriber can write “dispense as written” or “do not substitute” on the prescription. This legally blocks the pharmacist from swapping the drug. In 18 states, the doctor must also provide a written reason for this restriction, such as previous adverse reactions or clinical instability.

Why do some states ban substitution for certain drugs?

Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) have a very small margin between a therapeutic dose and a toxic one. Even slight changes in absorption-due to different inactive ingredients or manufacturing processes-can lead to treatment failure or serious side effects. States like Kentucky and Hawaii maintain lists of these drugs and prohibit substitution to prevent harm. Examples include warfarin, digoxin, and antiepileptic drugs.

How do I find out what my state’s laws are?

Visit your state’s board of pharmacy website. Most have a section on drug substitution laws, including rules for generics and biosimilars. You can also call them directly. The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP) offers a model law that many states follow, but your state may have unique rules. Don’t rely on national sources-your state’s law controls what happens at your local pharmacy.

Robin bremer

February 19, 2026 AT 22:30so like... i just got my levothyroxine switched last week and didn't even notice til i saw the damn pill color? 🤯 like wtf? i felt like a zombie for 3 days. my pharmacist said "it's the same thing" but no it's not. my body noticed. now i'm scared to even pick up refills. why do they not TELL us??

Maddi Barnes

February 20, 2026 AT 20:13Ohhhhh sweet mercy, this is why I always ask for the brand name even if it costs $200 more-I’ve had my thyroid crash twice because some pharmacist thought "it’s just a generic." 😒 And let me tell you, the FDA doesn’t get it-small molecule, big difference when your body’s been fine-tuned for years on one specific formulation. Also, why is it that 19 states think silence = consent? That’s not consent, that’s gaslighting with a pharmacy receipt.

Michaela Jorstad

February 21, 2026 AT 14:36I'm a pharmacist in Ohio, and I can tell you-we're caught between a rock and a hard place. Insurance forces us to substitute. Patients get mad when they feel weird. Doctors get mad when we don't document. And state laws? Half of them are outdated and written by lobbyists who've never held a pill bottle. I write "dispense as written" on every NTI script I can. It's the only way I sleep at night.

Davis teo

February 22, 2026 AT 02:31My mom died because they switched her warfarin without telling her. She didn't know to check. She didn't know to ask. And now? I scream at every pharmacy counter. I don't care if it's legal-I care that people are dying because of a paperwork loophole. This isn't about savings. This is about trust. And we lost it.

Robert Shiu

February 22, 2026 AT 02:55Hey, I get it-costs are insane. But here’s the thing: if you’re on meds that affect your brain, heart, or hormones, you’re not a number. You’re a human. And if your pharmacist doesn’t ask if you’re cool with the switch? That’s not efficiency. That’s negligence. I started asking for "dispense as written" on all my scripts. It’s a hassle? Yeah. But I’m alive. That’s the win.

Hariom Sharma

February 22, 2026 AT 15:38Bro, in India, we don't even have this problem-generics are the ONLY option! And guess what? People live just fine. Maybe the fear is more about marketing than science? I've been on generic antihypertensives for 8 years. No issues. Maybe the real problem is not the law-it's the fear-mongering?

Arshdeep Singh

February 24, 2026 AT 15:14Let’s be real-the FDA’s equivalence standards are a joke. They test bioavailability over 10 patients in a lab for 72 hours. Real people take these pills for decades with comorbidities, gut issues, liver problems. The data is garbage. And now we’re letting pharmacists play Russian roulette with our lives? This isn’t healthcare. It’s corporate roulette. And the states? They’re just the dealers.

Tommy Chapman

February 25, 2026 AT 02:11Why is everyone acting like this is a crisis? It’s a generic. You’re not dying because your pill is blue instead of yellow. Get over it. If you can’t afford your meds, that’s your problem. Not the pharmacist’s. Stop crying. We need savings. The system works-people are just too soft.

Chris Beeley

February 25, 2026 AT 05:12As a Nigerian physician who trained in the UK and now practices in Lagos, I can say with absolute authority: the American pharmaceutical system is a grotesque carnival of profit-driven chaos. In Nigeria, generics are the standard, and they’re monitored by the NAFDAC-rigorous, centralized, and transparent. Here? You’ve got 50 different state laws, pharmacists juggling 12 insurance forms, and patients who don’t even know their own meds. It’s not innovation. It’s institutionalized incompetence. The FDA’s Purple Book? A glorified spreadsheet. Real science? We’re decades behind. This isn’t healthcare. It’s a market simulation game with human lives as tokens.