When a brand-name drug’s patent runs out, prices don’t just drop-they collapse. Sometimes by 90%. That’s not speculation. It’s happened thousands of times. The question isn’t whether generics will come-it’s when. And for pharmaceutical companies, getting that timing wrong can cost hundreds of millions in lost revenue. For generic manufacturers, missing the window means wasting millions on failed drug development. Predicting generic entry isn’t guesswork. It’s a high-stakes science built on patents, regulations, and strategic behavior.

Why Timing Matters More Than You Think

The moment a drug loses patent protection, the market shifts overnight. The brand drug, once priced at $10,000 per year, might drop to $1,200 within 18 months. That’s not a slow decline. It’s a cliff. And companies that don’t see it coming lose billions. Take Humira, the top-selling drug in U.S. history. Its core patent expired in 2016, but generic versions didn’t hit the market until 2023. Why? Because AbbVie filed over 130 follow-up patents, creating what experts call a “patent thicket.” Each new patent delayed competition by months. That delay meant $20 billion in extra revenue for AbbVie. Meanwhile, generic companies sat on the sidelines, waiting for the legal chaos to clear. For brand companies, forecasting isn’t about predicting the future-it’s about controlling it. If you know generics are coming in 14 months, you can raise prices now, shift patients to a new formulation, or license your own generic to capture some of the market. If you wait until the patent expires, you’re already behind.The Legal Framework: Hatch-Waxman and ANDAs

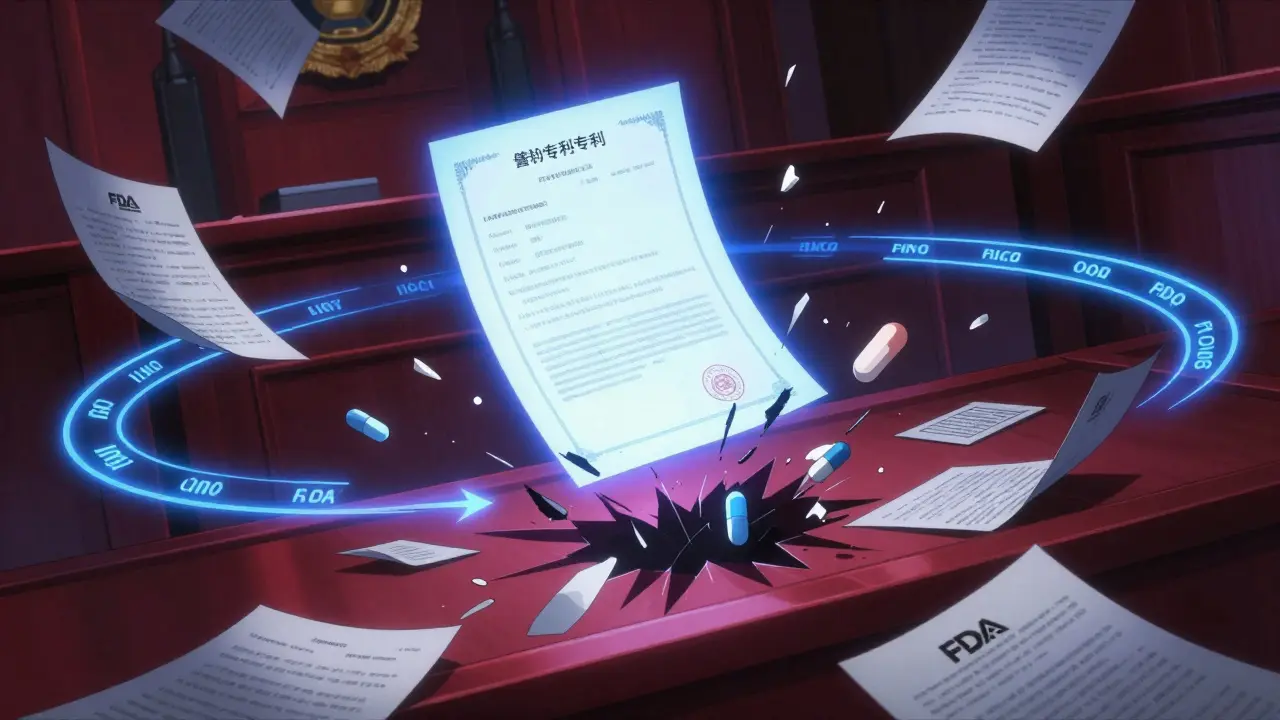

The whole system started with the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act. Before that, generic companies had to run full clinical trials to prove their drugs worked-costing years and millions. Hatch-Waxman changed that. It let generics submit an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), proving only that their version was bioequivalent to the brand. No need to repeat safety trials. Just prove it delivers the same amount of drug into the bloodstream at the same rate. But there’s a catch. To file an ANDA, the generic company must certify the patent status. One option is a Paragraph IV certification: “We believe this patent is invalid or won’t be infringed.” That’s the signal everyone watches. It’s like a starting gun. When a Paragraph IV is filed, brand companies usually sue. And when they sue, the FDA automatically delays approval for 30 months-unless a court rules otherwise. That’s why 42% of patent lawsuits delay generic entry by an average of 18.7 months.What Data Actually Predicts Entry?

You can’t just look at the patent expiration date and call it a day. That’s like predicting a storm by checking the calendar. Real forecasting uses 12+ data streams. Here’s what matters:- Patent listings in the FDA Orange Book: This is the official record of every patent protecting a drug. Each patent listed adds delay. On average, every extra patent pushes entry back by 4.2 months.

- Paragraph IV certifications: These are the clearest signals that a generic is preparing to challenge. 78% of first generics launch during their 180-day exclusivity window-so tracking who files matters.

- FDA approval timelines: The median time from ANDA submission to approval is 38 months. But that’s not fixed. In 2021-2022, pandemic backlogs added 7.2 months to approval times.

- Patent litigation outcomes: Courts don’t always side with the brand. If a patent is invalidated, entry can happen immediately. If it’s upheld, the delay continues.

- Market size: Drugs earning more than $1 billion a year attract generic competitors 11.3 months faster than smaller drugs. Money talks.

- Therapeutic equivalence codes: The FDA assigns codes like “AB” to show if a generic can be substituted. If substitution is allowed, prices drop faster. If not, the brand keeps some pricing power.

Why Some Drugs Take Longer Than Others

Not all drugs are created equal when it comes to generic entry. Small-molecule drugs-like pills and capsules-are relatively simple to copy. About 92% of them face generic competition within five years of patent expiry. Biologics? Totally different. These are complex proteins made in living cells-think Humira, Enbrel, or Humira’s successor, Skyrizi. Copying them isn’t like copying aspirin. It takes 12-18 months just to develop a biosimilar, and the FDA requires additional clinical data. That’s why only 38% of eligible biologics have biosimilar competitors, even years after exclusivity ends. Even among small molecules, some face delays. Oncology drugs, for example, take 32% longer to face generics than cardiovascular drugs. Why? Because oncology drugs often have complex dosing, multiple formulations, and tighter regulatory scrutiny. Plus, many are protected by multiple patents covering delivery methods, salt forms, and packaging.

How Generic Companies Choose When to Enter

Generic manufacturers don’t just rush in. They play a game. The first company to file a Paragraph IV certification gets 180 days of exclusive marketing rights. That’s huge. During that window, they’re the only generic on the market-and they can charge nearly as much as the brand. So companies wait. They analyze lawsuits. They study court rulings. They time their filings. Some wait until the brand sues, then file right after. Others file early, hoping to catch the brand off guard. But if they file too early and the patent is upheld, they lose their chance. It’s a high-risk, high-reward strategy. And then there’s the “authorized generic.” Sometimes, the brand company launches its own generic version-sold under a different label, often at a discount. This happens in 41% of cases. But only 22% of forecasting models predict it. That’s a blind spot. If you’re a generic company expecting to be first, and the brand slips in with its own version, you’re out of luck.The Hidden Delays: Product Hopping, REMS, and Citizen Petitions

There are sneaky ways brand companies extend exclusivity without new patents. Product hopping is one. A company switches patients from an old drug to a new version-say, from a tablet to a pill with a different coating or delivery system-just before the patent expires. The new version gets its own patent. The old one loses protection, but no one can switch back. In 63% of the top 100 drugs, this tactic extended market exclusivity by 18-24 months. REMS programs (Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies) are another. These are safety controls the FDA requires for risky drugs. But they can also block generics. If a brand’s REMS requires special training or monitoring, generics can’t distribute unless they replicate it. That process adds 14.3 months on average. Citizen petitions are legal requests-often filed by the brand-to delay approval. The FDA must respond, and that can take months. On average, these petitions delay generic entry by 7.1 months. They’re not always about safety. Sometimes they’re just about buying time.How Accurate Are the Forecasts?

Simple models that just use patent dates? They’re wrong about half the time. R² values of 0.42-0.51 mean they miss the mark by months, sometimes years. Advanced models-like those from Evaluate Pharma or IQVIA-use machine learning to analyze 15+ years of FDA approval data, litigation outcomes, and market trends. These models achieve R² values of 0.78-0.85. That’s a huge improvement. They predict first generic entry within a six-month window 89% of the time for small molecules. But even the best models can’t predict everything. In 2022, Harvard’s Dr. Aaron Kesselheim pointed out that AbbVie’s successful shift of Humira patients to Skyrizi reduced potential biosimilar market share by 35%. No algorithm could predict that kind of strategic behavior. Human decisions-marketing, patient loyalty, doctor influence-still matter.

What’s Changing in 2025-2026?

The game is evolving. The FDA’s new Competitive Generic Therapy (CGT) pathway, launched in 2023, gives 180-day exclusivity to generics for drugs with little or no competition. That’s a new variable forecasters are learning to track. The Inflation Reduction Act’s Medicare drug price negotiation rules, starting in 2025, could also change the game. If the government negotiates lower prices for certain drugs, generic companies might wait longer to enter-because the upside is smaller. Analysts at Morgan Stanley predict this could reduce price erosion by 15-20% for negotiated drugs. And AI is coming. Natural language processing tools are now scanning thousands of patent lawsuits, FDA letters, and court filings automatically. By 2026, AI-driven models are expected to cut prediction errors from 11.4 months to 6.8 months. That’s not just an improvement-it’s a revolution.What You Can Do Today

If you’re in pharma-whether you make brand drugs or generics-here’s what to do:- Start tracking 36-48 months before patent expiry. Don’t wait.

- Use the FDA Orange Book. Check it weekly. Look for Paragraph IV certifications.

- Monitor patent litigation. If a case is dismissed or a patent is invalidated, entry can happen fast.

- Know your therapeutic class. Oncology and complex generics take longer.

- Account for state substitution laws. California’s rules are different from Texas’s. That affects pricing speed.

- Watch for authorized generics. They’re hidden, but they happen often.

Gregory Parschauer

January 14, 2026 AT 00:36Let’s be real-this whole system is a rigged casino where Big Pharma holds all the cards. Patent thickets? Product hopping? Citizen petitions? These aren’t legal strategies, they’re corporate extortion tactics wrapped in legalese. And don’t get me started on authorized generics-brand companies playing both sides while pretending they’re ‘innovating.’ The FDA’s complicit. Congress is bought. Patients pay the price. This isn’t healthcare-it’s a profit-maximization scheme dressed in white coats.

And you call this ‘science’? Nah. This is predatory capitalism with a PhD.

Anyone who thinks market forces alone will fix this is delusional. We need public drug manufacturing. Period.

mike swinchoski

January 15, 2026 AT 14:29Patents expire, generics come in, prices drop. That’s it. Why make it so complicated? You’re overthinking this like it’s rocket science. It’s just business. If you can’t handle competition, don’t make drugs.

Trevor Whipple

January 17, 2026 AT 09:20yo so i was reading this and like… did u know that the 180 day exclusivity for first filers is actually a total scam? like, sometimes the first filer and the brand company are in cahoots and they just split the market. no one talks about this. i saw it happen with a statin in 2020. the generic came out, price dropped 80%, but then the brand launched their own ‘discount’ version right after and guess what? same damn price. total fraud.

also, the FDA takes 38 months on avg? bro that’s insane. my cousin works at a compounding pharmacy and they can make a bioequivalent version in 6 weeks if they wanted to. it’s all about control, not science.

Lance Nickie

January 19, 2026 AT 01:23Wrong. Biosimilars are fine. The real problem is the FDA letting brands game the system with REMS and citizen petitions. Just abolish those.

Milla Masliy

January 19, 2026 AT 22:17I really appreciate how thorough this breakdown is. Coming from India, where generic access is the backbone of our healthcare system, I see firsthand how critical timing and legal strategy are-not just for profits, but for lives.

What’s fascinating is how the US system creates artificial scarcity, while countries like Canada and India produce generics faster and cheaper because they don’t have the same patent litigation culture. The cultural difference in how innovation is valued here vs. there is striking.

Also, the point about state substitution laws? Huge. In California, pharmacists can swap without doctor approval-so prices drop faster. In Texas, not so much. That’s policy, not science. We need national uniformity.

Damario Brown

January 20, 2026 AT 04:10lol you guys act like this is news. i’ve been tracking ANDA filings since 2018. the real story? 60% of paragraph iv certifications are filed by the same 5 generic companies. it’s an oligopoly disguised as competition. and guess who owns the top 3? big pharma subsidiaries. so yeah, the brand company ‘gets undercut’… by their own offshore subsidiary.

also, the ‘180 day exclusivity’? more like 180 days of monopoly pricing while the brand quietly shifts patients to skyrizi. the data doesn’t lie-this whole system is designed to funnel cash into the same pockets.

and don’t even get me started on how ‘therapeutic equivalence’ codes are manipulated. ab = ‘substitutable’? sure. until the brand changes the pill color and the pharmacy won’t swap. it’s psychological branding disguised as regulation.

sam abas

January 20, 2026 AT 09:37Okay, let’s cut through the noise. Everyone’s focused on patents and litigation, but nobody’s talking about the elephant in the room: the fact that most of these drugs were developed with public funding. The NIH, CDC, and taxpayer dollars paid for the foundational research on Humira, Lipitor, you name it. Then private companies patent it, jack up the price, and then cry when generics come in.

And you’re telling me we need AI models to predict entry? Why not just nationalize the damn patents? If the government funded it, the public should own it. We’re not in 1984 anymore. The Hatch-Waxman Act was already a betrayal of public interest. Now we’re just polishing the same broken system with machine learning.

Also, ‘product hopping’? That’s not innovation. That’s fraud. A pill with a different coating isn’t a new drug-it’s a marketing trick. The FDA should ban it. But they won’t because the lobbyists pay their salaries.

And the ‘authorized generic’ loophole? That’s not competition. That’s collusion. The brand company gets to keep 80% of the market while pretending they’re ‘helping’ patients with a cheaper version. It’s a psychological trick to soften the blow of generic entry. And we’re all supposed to be impressed by how ‘smart’ the forecasting models are? No. We’re supposed to be angry.

Priyanka Kumari

January 22, 2026 AT 07:24This is such an important read for anyone in global health. In India, we’ve been making affordable generics for decades-but even we face challenges when U.S. patents block export. I’ve seen patients in rural Bihar wait months because a life-saving drug is patented in America.

One thing I’d add: the real hero here isn’t the AI model or the patent attorney-it’s the generic manufacturers in Hyderabad and Chennai who risk everything to produce these drugs. They don’t have lawyers or lobbyists. Just grit.

Also, the point about biosimilars? Absolutely true. In India, we’ve made biosimilars for Humira at 1/10th the cost, but the U.S. regulatory maze makes it nearly impossible to enter. It’s not about science-it’s about protectionism.

Let’s stop pretending this is about innovation. It’s about access. And access shouldn’t be a privilege.

Avneet Singh

January 23, 2026 AT 04:34Everyone’s missing the forest for the trees. The real issue isn’t patent thickets or REMS-it’s that the entire regulatory framework was designed for 20th-century pharmaceuticals. We’re now in the age of RNA therapeutics, CRISPR-based drugs, and AI-driven molecule design. The Orange Book? It’s a paper ledger. The ANDA process? A fax machine in the digital age.

And you think AI models will fix this? They’re just automating the same flawed logic. What we need is a complete overhaul: open-source drug development, public patent pools, and mandatory data sharing. But no-because that would threaten the $1.5 trillion pharma empire.

Also, ‘180-day exclusivity’? That’s a corporate welfare program disguised as competition. It’s not a reward for innovation-it’s a bribe to delay market entry. The system is broken at its core. And no algorithm can fix that.