Opioid Hyperalgesia vs Tolerance Checker

Check for Opioid Hyperalgesia

This tool helps clinicians identify key differences between opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) and tolerance based on clinical patterns. Select all symptoms that match your patient's presentation.

When More Opioids Make Pain Worse

It’s one of the most confusing problems in chronic pain care: a patient is on higher and higher doses of opioids, but their pain isn’t getting better-it’s getting worse. Doctors often assume this is opioid tolerance, so they keep increasing the dose. But what if the problem isn’t that the medicine isn’t working anymore? What if it’s actually making the pain more intense?

This isn’t rare. It’s called opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH), and it’s when long-term opioid use causes the nervous system to become oversensitive to pain. The body starts reacting to even light touches or normal movements as painful. It’s the opposite of what you’d expect from a painkiller.

Many clinicians still miss it. They see rising doses and worsening pain and think, “The patient needs more.” But in OIH, giving more opioids makes things worse. And if you don’t recognize the difference between OIH and tolerance, you’re not just failing the patient-you’re making their pain worse.

What’s the Difference Between OIH and Tolerance?

At first glance, they look the same. Both involve needing higher doses over time. But the reasons behind them are completely different.

Opioid tolerance means the body gets used to the drug. The same dose doesn’t block pain like it used to. So you increase the dose to get back to the same level of relief. This happens with all opioid effects-pain relief, drowsiness, even nausea. Tolerance doesn’t make pain more sensitive. It just makes the drug less effective.

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia is a whole different beast. Here, the opioid isn’t losing its effect-it’s actively causing the nervous system to amplify pain signals. The patient doesn’t just feel their original pain more intensely. They start feeling pain in new places. A person with low back pain might suddenly feel burning in their feet. A simple brush of clothing against the skin causes sharp pain-that’s allodynia, a classic sign of OIH.

Think of it this way: tolerance is like a car engine losing power. You need more fuel to go the same speed. OIH is like the engine starts revving uncontrollably on its own, even when you’re not pressing the gas.

Red Flags That Point to OIH, Not Tolerance

Here’s what to look for when a patient’s pain is getting worse on higher opioid doses:

- Pain spreads to new areas-like from the lower back to the legs or arms. Tolerance keeps pain in the same place.

- Pain changes quality-sharp, burning, or electric sensations appear where there was only dull aching before.

- Allodynia develops-light touch, wind, or bed sheets cause pain. This rarely happens with tolerance alone.

- Pain gets worse when you increase the dose-if higher doses make pain worse instead of better, OIH is likely.

- Pain doesn’t improve with dose reduction-in tolerance, lowering the dose usually makes pain worse. In OIH, lowering the dose can actually help.

One of the biggest clues? The patient says, “I’m on more pills than ever, but I hurt more.” That’s not tolerance. That’s OIH.

Why This Gets Missed So Often

There’s no blood test for OIH. No scan shows it. It’s diagnosed by pattern recognition-and most doctors aren’t trained to look for it.

For years, the medical community doubted it even existed. Early studies were done in labs with animals. It wasn’t until the 2000s that clinicians started seeing it in real patients. Even now, some think it’s just withdrawal or addiction.

But here’s the thing: OIH isn’t about craving or withdrawal. It happens even when the patient is on a stable dose. A person might feel worse pain on day 10 of their current dose, not when they’re cutting back. That’s not dependence. That’s neurobiology.

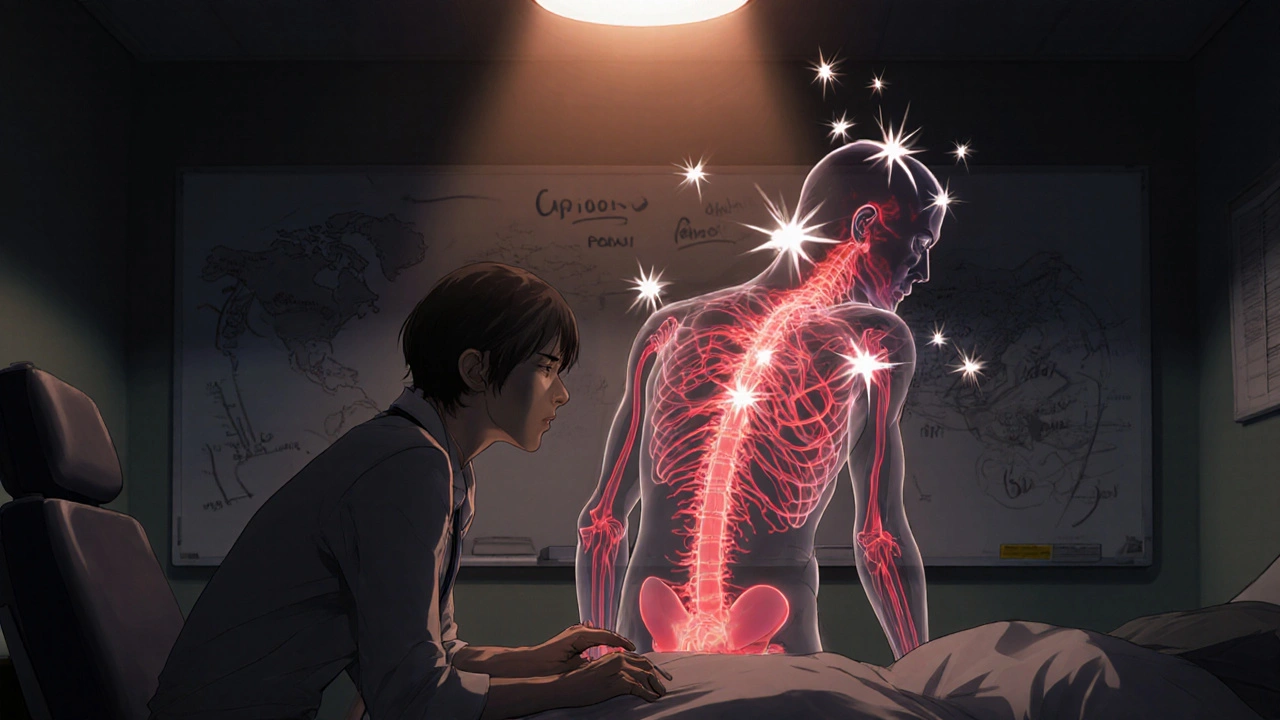

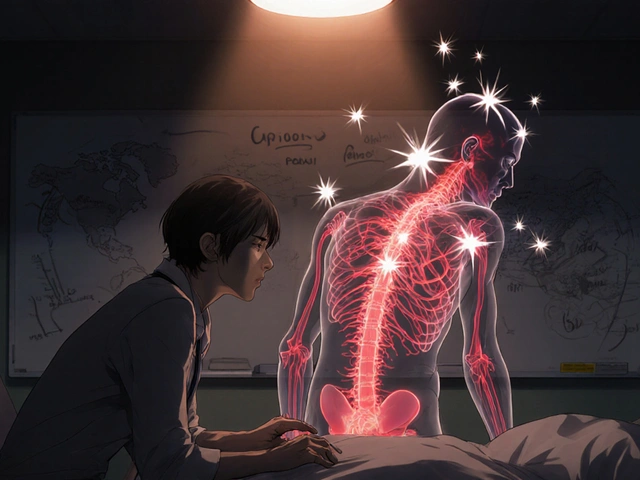

Studies show OIH is linked to changes in the spinal cord-NMDA receptors get overactive, glial cells flare up, and pain signals get amplified. It’s not psychological. It’s physical. And it’s reversible.

How to Diagnose It in Practice

You don’t need fancy tools to spot OIH. You just need to ask the right questions and track the details.

- Map the pain-have the patient draw where it hurts at every visit. If the area keeps expanding, that’s a red flag.

- Track dose vs. pain-keep a simple log: “On 60mg oxycodone, pain was 5/10. On 90mg, pain rose to 7/10.” That pattern screams OIH.

- Check for allodynia-gently touch the skin with a cotton swab. If they flinch or say it hurts, that’s a clinical clue.

- Look at timing-did the pain worsen after a dose increase, or after being on the same dose for months? OIH often builds slowly.

Some clinics use quantitative sensory testing (QST), which measures how the body responds to heat, cold, or pressure. But you don’t need that to start suspecting OIH. Just pay attention to the story the patient tells.

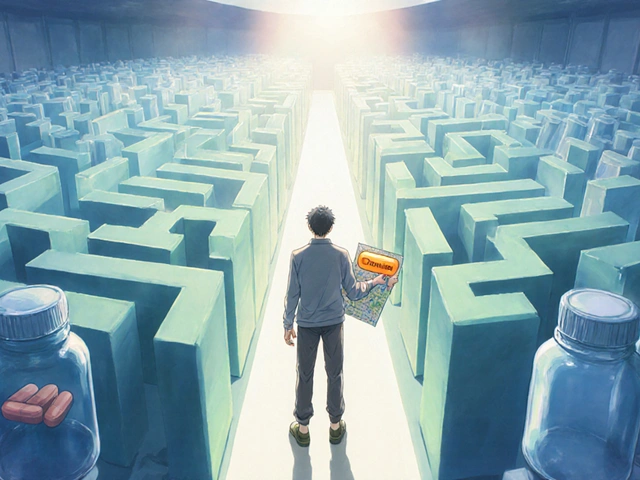

What to Do When You Suspect OIH

If you think it’s OIH, don’t reach for a higher dose. That’s the worst thing you can do.

Here’s what works:

- Slowly reduce the opioid dose-even cutting by 10-20% can lead to noticeable pain improvement in weeks. It feels counterintuitive, but it works.

- Switch opioids-some patients respond better to methadone or buprenorphine, which have different effects on NMDA receptors.

- Add an NMDA antagonist-medications like low-dose ketamine or dextromethorphan can help block the overactive pain pathways. This isn’t experimental-it’s used in pain clinics.

- Introduce non-opioid options-gabapentin, duloxetine, physical therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy all help reduce pain without worsening OIH.

One real-world example: a patient with chronic back pain on 120mg oxycodone daily. Pain was at 8/10. After switching to buprenorphine and cutting oxycodone by 50%, their pain dropped to 4/10 in six weeks. Allodynia disappeared. They didn’t need more opioids-they needed fewer.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

OIH isn’t just a side effect. It’s a driver of the opioid crisis.

When patients don’t get better, doctors keep prescribing more. More prescriptions mean more risk of dependence, overdose, and addiction. But if OIH is the real problem, then the solution isn’t more pills-it’s a smarter approach.

Guidelines from New Zealand’s Medsafe, the FDA, and the EMA now warn against long-term opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. Why? Because the risks-OIH, tolerance, addiction-often outweigh the benefits.

Prescriptions for opioids in New Zealand dropped 17% between 2018 and 2021. That’s not just policy change. That’s doctors learning to see OIH for what it is: a treatment-induced problem, not a disease progression.

Final Thought: Don’t Just Prescribe. Observe.

Chronic pain is complex. Opioids can help-but only if you know when to stop.

The key isn’t knowing every detail of neurobiology. It’s paying attention. If your patient’s pain is spreading, changing, or getting worse with higher doses, pause. Ask: Is this tolerance-or is it OIH?

Because the answer changes everything.

Can opioid hyperalgesia happen with low doses?

Yes. While OIH is more common with high-dose, long-term use, it can develop even at moderate doses after several months. It’s not about the amount-it’s about how the nervous system responds over time. Some patients show signs after just 2-3 months on opioids.

Is OIH the same as addiction?

No. Addiction involves compulsive drug use despite harm, cravings, and loss of control. OIH is a physiological change in pain processing. A patient can have OIH without craving opioids, and they can be addicted without having OIH. The two can overlap, but they’re separate conditions.

Can OIH be reversed?

Yes. Many patients see significant improvement within weeks of reducing opioid doses or switching medications. Pain sensitivity often returns to baseline, especially when combined with non-opioid therapies like physical therapy or nerve-targeted medications.

What’s the best way to taper opioids if OIH is suspected?

Slow and steady works best. Cut by 10% every 1-2 weeks, and monitor pain levels closely. Don’t rush-too fast can trigger withdrawal. Use non-opioid supports like gabapentin or cognitive behavioral therapy to help manage discomfort during tapering.

Are there any medications that make OIH worse?

Yes. Long-acting opioids like methadone or fentanyl patches can sometimes worsen OIH because of their prolonged action on NMDA receptors. Also, combining opioids with certain antidepressants or anticonvulsants without proper monitoring can interfere with pain signaling. Always reassess the full medication list when OIH is suspected.

Brittney Lopez

November 1, 2025 AT 06:20This is such an important post-I’ve seen so many patients spiral because doctors just kept upping the dose. I work in primary care and we’re finally starting to catch on. One lady told me, ‘I’m on more pills than ever but I can’t even sleep without my sheets hurting me.’ That’s OIH, not tolerance. Thank you for putting this out there.

Jens Petersen

November 2, 2025 AT 11:28Oh for fucks sake. Another ‘opioids are evil’ diatribe wrapped in medical jargon. You think this is revolutionary? The neurobiology of OIH was published in *Nature Neuroscience* in 2006. But no-instead of addressing the real crisis-overprescribing by clueless GPs who treat pain like a checkbox-you’re turning this into some kind of moral parable. Pathetic.

Keerthi Kumar

November 3, 2025 AT 03:30Thank you for this. In India, we have a terrible habit of giving opioids like candy-for back pain, for headaches, for ‘stress.’ No one asks why the pain is there. No one checks for allodynia. I once saw a man on 180mg oxycodone daily, crying because his own shadow hurt him. His doctor said, ‘Maybe try 200mg.’ We need education-not just in clinics, but in medical schools. OIH isn’t a Western problem-it’s a human problem. And we’re failing.

Dade Hughston

November 4, 2025 AT 08:57so like i was on oxycodone for like 3 years for my herniated disc and i started getting this weird burning in my hands and my dog licking me made me scream and i thought i was losing my mind but my dr just kept saying you need more and i was like bro i feel like my nerves are on fire and then i cut down to like 10mg and like 3 weeks later i could touch my pillow again and i was like wait what did you just do to me

Jim Peddle

November 6, 2025 AT 07:35Let’s be honest. This is just a pretext to reduce opioid prescribing under the guise of ‘clinical insight.’ The FDA and EMA have been pushing this narrative for years. Who benefits? Pharma companies selling ketamine and gabapentin. The data on OIH reversal is anecdotal at best. And the ‘pain mapping’? That’s not evidence-it’s storytelling.

S Love

November 7, 2025 AT 02:51Excellent breakdown. I’m a physical therapist who’s seen patients recover from OIH after tapering-some with just 20 minutes of graded exposure therapy and breathing retraining. The body can recalibrate. It’s not magic. It’s neuroplasticity. But it requires patience, and doctors who listen. This post should be required reading for every resident in pain medicine.

Pritesh Mehta

November 7, 2025 AT 09:01Western medicine continues its obsession with chemical solutions to complex human conditions. In ancient Ayurveda, pain was never treated as a standalone entity-it was seen as imbalance, a sign of disturbed prana. Opioids are a blunt instrument, a colonial tool imposed on bodies that were never meant to be medicated into silence. You reduce the dose? Good. But you must also restore the rhythm-diet, breath, movement. No pill, no matter how clever, can replace the wisdom of the body.

Billy Tiger

November 9, 2025 AT 02:03My uncle died of an overdose on 150mg a day. They said he was tolerant. He was in agony. They kept giving him more. Now I know it was OIH. This is why I hate the system. They don’t care. They just want to write prescriptions and get paid. And now you want us to trust them again? Fuck that.

Katie Ring

November 10, 2025 AT 01:19It’s not just about pain-it’s about control. The medical system fears losing power. If you admit opioids cause more pain, you admit you’ve been wrong for decades. And admitting that means you have to change. And change is scary. So you double down. You call it tolerance. You call it addiction. You don’t call it what it is: iatrogenic suffering.

Adarsha Foundation

November 11, 2025 AT 11:53Thank you for writing this with such clarity. I’ve had patients who felt ashamed to say their pain got worse on higher doses-they thought they were being weak or drug-seeking. This post gives them language. And language is the first step toward healing. I’ll be sharing this with my team tomorrow.