Every year, thousands of people end up in the hospital not because of a bad fall or a serious illness, but because they took something they thought was completely safe: an over-the-counter pain reliever. The culprit? Acetaminophen. It’s in Tylenol, Excedrin, NyQuil, Sudafed, and more than 600 other medications. Most people don’t realize how easy it is to accidentally overdose - especially if they’re taking more than one product at a time.

Why Acetaminophen Is a Silent Threat

Acetaminophen is not dangerous when used correctly. In fact, it’s one of the safest pain relievers for people with liver disease - if you stick to the limits. But when you go over those limits, even just a little, your liver starts to get damaged. The problem isn’t the drug itself. It’s what happens inside your body when you take too much.

When you swallow acetaminophen, your liver breaks it down. Most of it turns into harmless waste. But a small portion becomes a toxic chemical called NAPQI. Normally, your liver neutralizes this toxin with a substance called glutathione. But if you take too much acetaminophen - say, more than 4,000 mg in one day - your glutathione runs out. That’s when NAPQI starts killing liver cells.

The scary part? You won’t feel it right away. No burning stomach. No dizziness. Just mild nausea or fatigue. By the time your skin turns yellow or your urine turns dark, it’s often too late. In the U.S., acetaminophen causes more than 56,000 emergency room visits every year. About 450 people die from it. Most of those cases aren’t suicide attempts. They’re mistakes.

The Real Danger: Hidden Acetaminophen

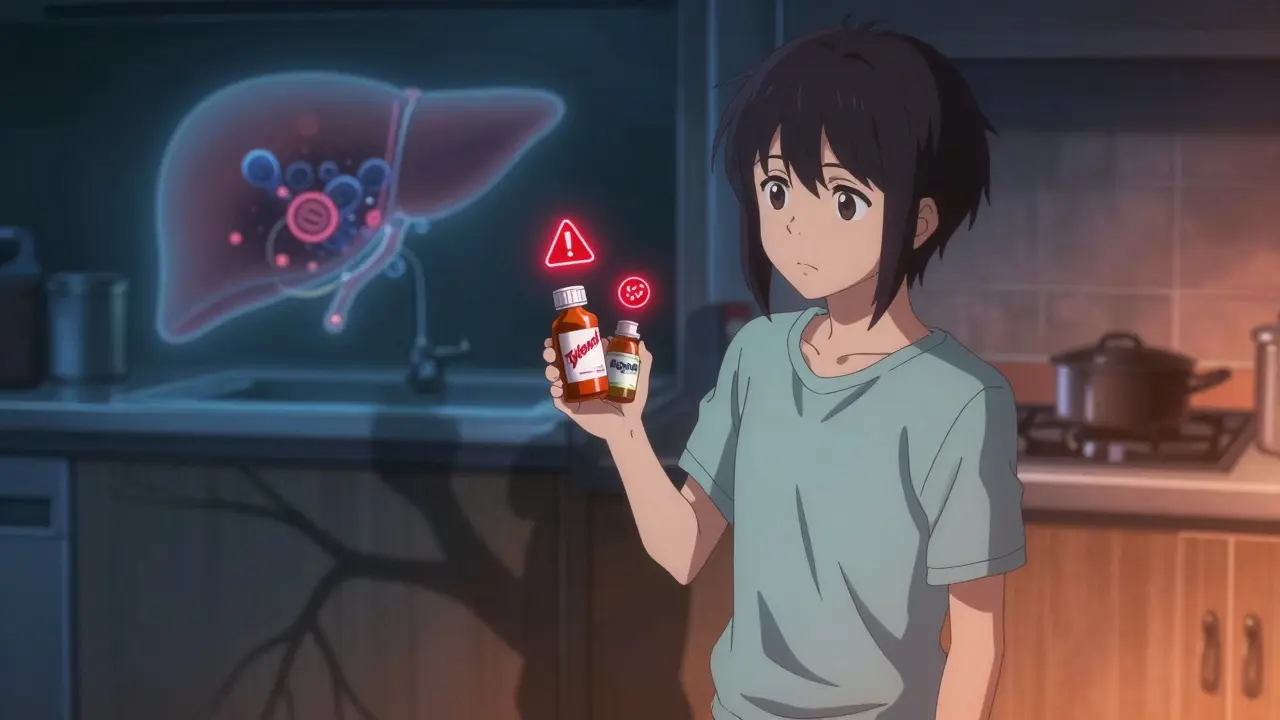

Most people think they’re safe because they only take one Tylenol. But here’s the trap: acetaminophen is hiding in plain sight.

- Excedrin contains acetaminophen - and aspirin, and caffeine.

- NyQuil and DayQuil? Both have it.

- Some cold and flu tablets? Acetaminophen.

- Prescription painkillers like Vicodin or Percocet? They’re mixed with acetaminophen too.

If you take Tylenol for a headache and then take NyQuil for a cold, you’re doubling your dose. And you might not even know it. The FDA says about 25% of unintentional overdoses happen because people didn’t realize they were taking acetaminophen in more than one product.

Always read the “Active Ingredients” section on the label. Look for “acetaminophen,” “paracetamol,” or “APAP.” If you see any of those, you’re taking it. Don’t assume it’s safe just because it’s sold over the counter.

Dosage Rules You Can’t Ignore

There’s no one-size-fits-all number. Your safe limit depends on your health.

- Healthy adults: Maximum 4,000 mg per day. That’s eight 500 mg pills. But even this is risky if you drink alcohol.

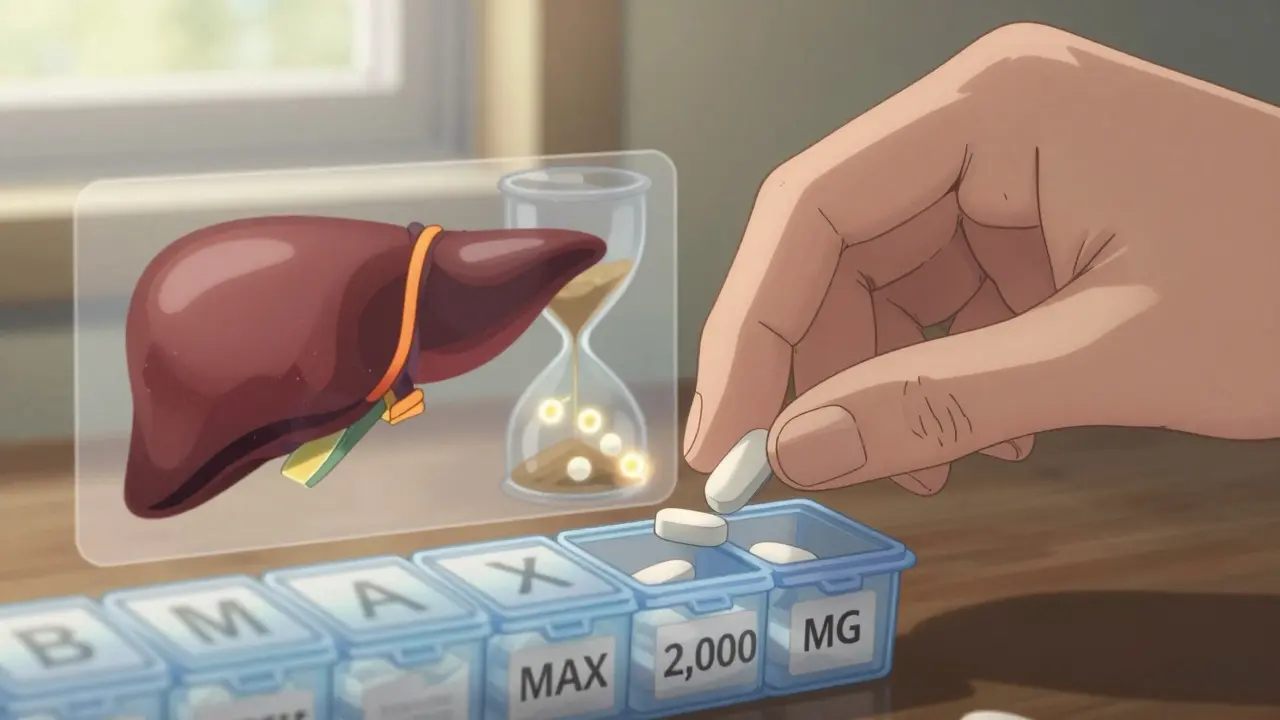

- People with liver disease: Do not exceed 2,000 mg per day. That’s four 500 mg pills. Some experts say even less.

- If you drink alcohol: Your safe limit drops to 2,000 mg - or less. Alcohol depletes glutathione, so your liver can’t handle even normal doses.

- Older adults or underweight people: Your body processes drugs slower. Stick to 3,000 mg max.

Also, never take a dose more often than every 6 hours. Spacing doses out by 8 hours is even safer. Taking four pills every 4 hours? That’s 4,000 mg in 12 hours - way too fast. Your liver doesn’t get time to recover.

NSAIDs Aren’t the Answer Either

People often switch to ibuprofen or naproxen thinking they’re safer for the liver. But that’s not true.

NSAIDs like Advil, Aleve, and diclofenac don’t usually hurt the liver directly. But they can wreck your kidneys, cause stomach ulcers, and raise blood pressure. For someone with liver disease, especially cirrhosis, NSAIDs can cause dangerous fluid buildup and kidney failure.

The American Liver Foundation says NSAIDs are “particularly discouraged” in advanced liver disease. So don’t trade one risk for another.

If you need pain relief and have liver problems, topical NSAIDs - gels or patches applied to the skin - are a better choice. They don’t enter your bloodstream the same way, so they’re much gentler on your liver and kidneys.

What to Do If You’ve Taken Too Much

If you think you’ve taken too much acetaminophen - even if you feel fine - act immediately.

Call poison control or go to the ER. Don’t wait for symptoms. The antidote, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), works best if given within 8 hours of overdose. After 16 hours, it’s far less effective. By 24 hours, liver damage may already be irreversible.

Don’t rely on “I’ll just sleep it off.” Acetaminophen overdose doesn’t wake you up with a hangover. It quietly kills your liver while you sleep.

Signs Your Liver Is Under Stress

Know these symptoms. They don’t always show up right away, but if you’ve taken extra doses, watch for them:

- Nausea or vomiting

- Loss of appetite

- Fatigue that won’t go away

- Pain in the upper right side of your abdomen

- Dark urine

- Clay-colored stools

- Yellowing of the skin or eyes (jaundice)

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases says 93% of acetaminophen-related liver failures show these signs within 24 to 72 hours. If you have any of these and took acetaminophen in the last day or two, get checked - now.

How to Stay Safe Long-Term

Prevention is simple, but it takes discipline.

- Keep a medication log. Write down every pill you take - even OTC ones. Include the time and dose. Use a notebook or your phone.

- Use a pill organizer. Buy one with daily compartments and write “MAX 2,000 MG” on the lid if you have liver disease.

- Never mix alcohol with acetaminophen. Not even one drink. Not even once.

- Ask your pharmacist. When you pick up a new prescription, ask: “Does this contain acetaminophen?”

- Check every bottle. Even if you’ve taken it before, manufacturers change formulas. Always re-read the label.

- Consider non-drug options. For chronic pain, try physical therapy, acupuncture, or cognitive behavioral therapy. The American Liver Foundation says these are safer first steps.

What’s Changing - And What to Watch For

The FDA now requires all OTC acetaminophen products to have a bold “Liver Warning” on the front label. That’s new since 2022. And the maximum daily dose on prescription combos has dropped from 4,000 mg to 3,250 mg.

Some companies are testing genetic tests to see who’s more at risk. If you have certain gene variations (like in glutathione S-transferase), your liver may break down acetaminophen slower. Companies like 23andMe now offer this as an add-on test.

And research is moving toward new pain relievers that don’t go through the liver at all. The NIH is spending $47 million on this by 2028. But for now, the safest thing is to know your dose - and stick to it.

Final Thought: It’s Not About Fear. It’s About Awareness.

You don’t need to avoid acetaminophen. You just need to respect it. It’s not a candy. It’s a powerful drug that your liver has to work hard to process. One extra pill. One extra drink. One hidden ingredient in a cold medicine. That’s all it takes.

Read labels. Track doses. Ask questions. If you have liver disease, be extra careful - even if you feel fine. Your liver doesn’t complain until it’s too late.

Ian Long

January 10, 2026 AT 02:49Man, I had no idea Tylenol could be this dangerous. I’ve been popping two every time my back flares up, plus NyQuil at night. Guess I’m lucky I haven’t ended up in the ER yet. Time to read labels like my life depends on it-because it kinda does.

Angela Stanton

January 10, 2026 AT 14:05Acetaminophen metabolism is a CYP2E1-mediated process, and NAPQI accumulation occurs when hepatic glutathione reserves drop below 30% of baseline. The FDA’s 4g/day limit is outdated-pharmacokinetic modeling shows 3g/day is safer for non-alcohol users, and 1.5g/day for those with BMI >30 or NAFLD. Also, APAP is metabolized via sulfation in children, which alters toxicity thresholds. 🧬⚠️

Johanna Baxter

January 10, 2026 AT 19:21So basically we’re all just one cold medicine away from dying in our sleep?? 😭 I took DayQuil last week and then a Tylenol for my headache. I’m gonna cry in the shower now. My liver is sobbing.

Jerian Lewis

January 10, 2026 AT 21:45People treat OTC meds like candy because they’re cheap and legal. But if it’s strong enough to kill your liver, it’s not ‘just a pill.’ We’ve normalized ignorance. And now we’re paying for it in ICU beds.

Kiruthiga Udayakumar

January 12, 2026 AT 20:39My mom in India died from liver failure after taking 3 painkillers for a fever. No one told her they had acetaminophen. This needs to be taught in schools. Not just here-everywhere.

Patty Walters

January 13, 2026 AT 22:44PSA: if you’re on any meds for chronic pain, ask your pharmacist to do a med review. They’ll catch hidden acetaminophen in your prescriptions. I did this last year and found I was taking 3,800mg/day without realizing it. Changed my life. 😌

Phil Kemling

January 13, 2026 AT 22:59It’s not just about dosage-it’s about our relationship with pain. We medicate discomfort instead of listening to it. The liver doesn’t scream. It just stops working. Maybe the real problem isn’t the drug, but our refusal to sit with the ache.

Maggie Noe

January 15, 2026 AT 15:39My dad took 3 Vicodin and a NyQuil after his surgery. He didn’t know both had APAP. He was fine… until he wasn’t. Liver transplant at 52. Now he drinks herbal tea and does yoga. I still don’t trust OTC meds. 🙏

Gregory Clayton

January 17, 2026 AT 11:08Why the hell is this even a thing? In my country, you need a prescription for anything that can kill you. Here? You can buy a death pill next to the gum. This is why America’s dying.

Catherine Scutt

January 19, 2026 AT 10:06So you’re telling me I can’t take my pain meds with wine? That’s not a warning. That’s a punishment. 🤷♀️

Darren McGuff

January 21, 2026 AT 09:20Topical NSAIDs are a game-changer. I’ve had chronic knee pain for 10 years. Used to take 400mg ibuprofen daily. Switched to diclofenac gel-no GI issues, no liver stress. My doctor didn’t even mention it. Shame.

Alicia Hasö

January 21, 2026 AT 11:31If you’re reading this and you’re managing chronic pain, please don’t wait until it’s too late. Talk to a physical therapist. Try acupuncture. Explore mindfulness. Your body is trying to tell you something. Medication isn’t the only language it speaks.

Ashley Kronenwetter

January 21, 2026 AT 20:21For those with liver disease: always carry a list of your medications. Emergency responders need to know what you’ve taken. I’ve seen too many cases where the only clue was a half-empty bottle on the nightstand.

Heather Wilson

January 23, 2026 AT 15:07It’s funny how people panic about vaping but ignore the fact that their daily Tylenol is a silent killer. The system’s broken. Labels are buried. Warnings are tiny. And the FDA lets it slide. You’re not safe because it’s ‘over the counter.’ You’re safe because you’re careful. Most aren’t.