Opioid Nausea Management Guide

Symptom Assessment

Patient Factors

Select symptoms and patient factors to get personalized recommendations.

When patients start opioids for pain, nausea and vomiting aren’t just annoying-they can stop treatment before it even works. About one in three people on opioids get sick to their stomach, and for many, it’s the #1 reason they quit taking their meds. Worse, some antiemetics used to treat this nausea can make other opioid side effects worse-or even be deadly when mixed. This isn’t about guessing what works. It’s about knowing which drugs to use, when, and why.

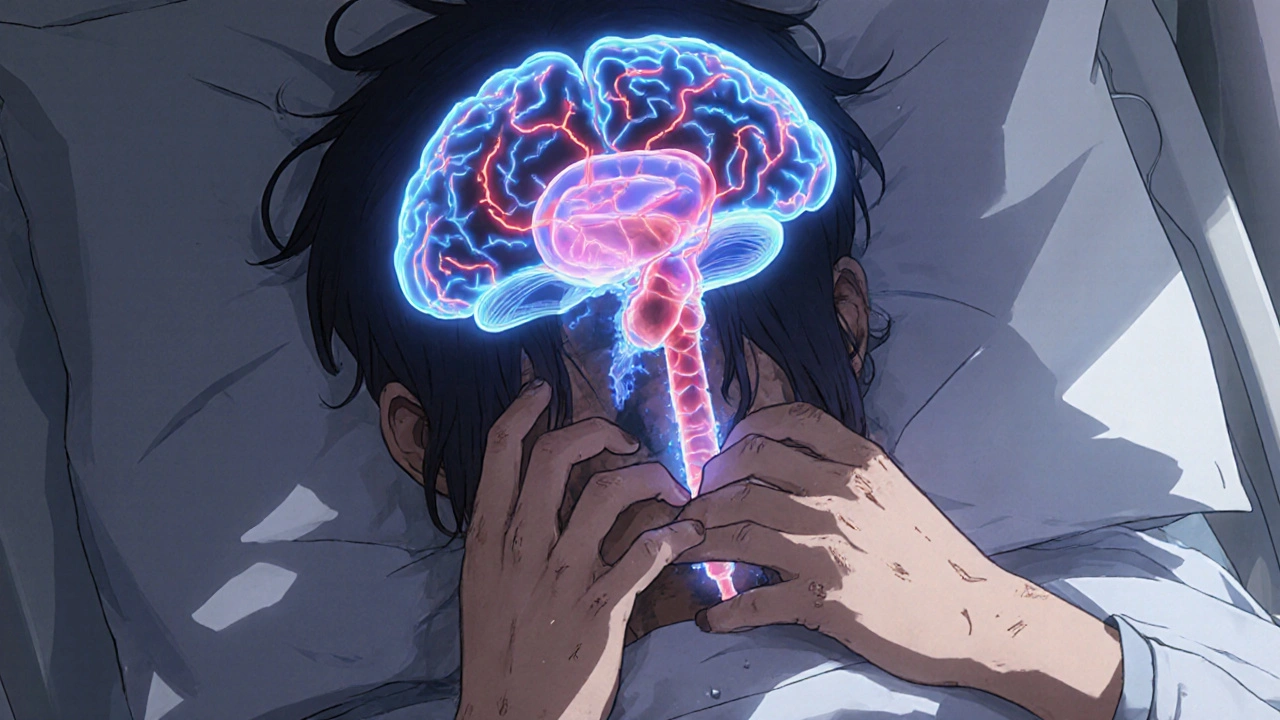

Why Opioids Make You Nauseous

Opioids don’t just dull pain. They also mess with your brain’s nausea control center and slow down your gut. The chemoreceptor trigger zone in your brainstem has dopamine receptors. When opioids bind there, they send false signals that your body is poisoned. At the same time, opioids bind to mu-receptors in your intestines, slowing digestion so much that your stomach overfills and triggers vomiting. Some people also get dizzy or feel off-balance because opioids affect the inner ear’s balance sensors.This isn’t the same as motion sickness or food poisoning. It’s opioid-induced nausea and vomiting (OINV), and it hits hardest in the first few days. Most people build tolerance within 3 to 7 days-if they don’t quit because they’re too sick. But if you’re not prepared, you might stop your pain meds altogether, and that’s when real problems start.

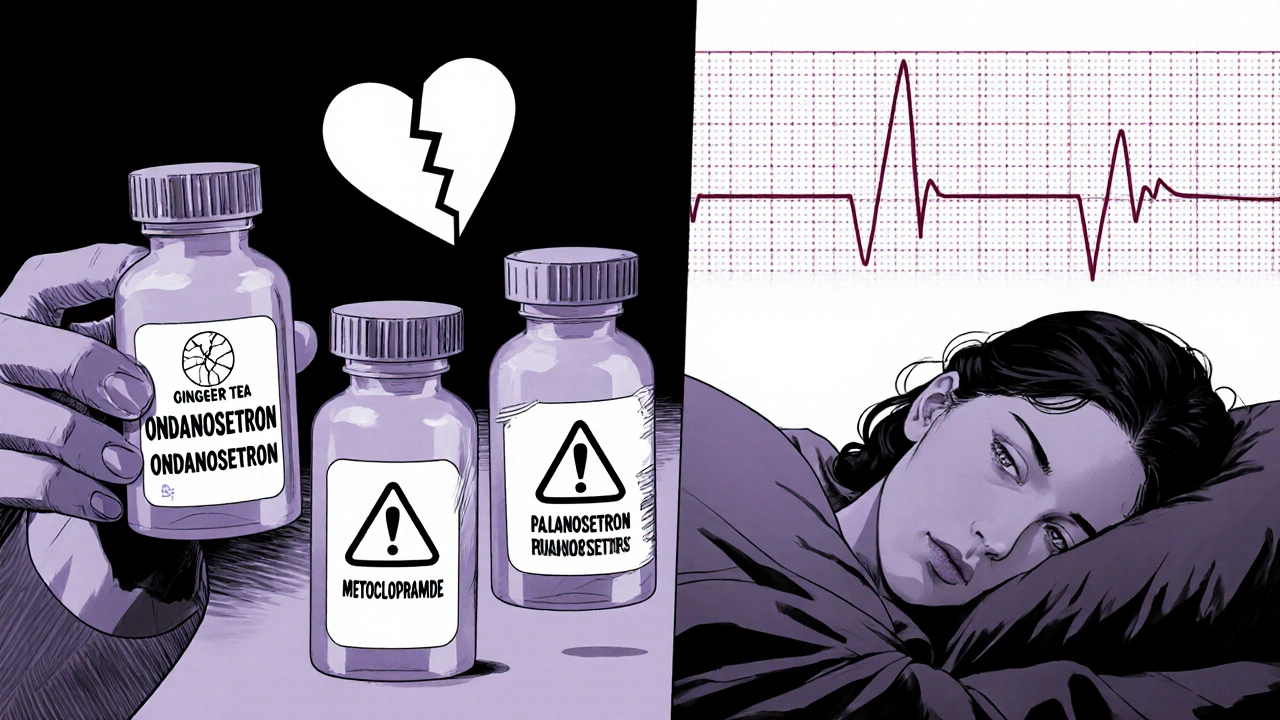

Common Antiemetics and Their Risks

Not all antiemetics are created equal. Some help. Some don’t. And a few can kill.Ondansetron (Zofran) blocks serotonin in the gut and brain. Studies show 8 mg and 16 mg doses work well for treating OINV. But it comes with a black box warning: it can lengthen the QT interval on your ECG, leading to dangerous heart rhythms. This risk goes up if you’re older, have heart disease, or take other drugs that affect your heart rhythm.

Palonosetron (Aloxi) is a newer version of ondansetron. In one study, only 42% of patients on palonosetron had nausea or vomiting compared to 62% on ondansetron. It lasts longer and may be more effective, but it’s also more expensive and still carries the same cardiac risk.

Metoclopramide (Reglan) boosts gut movement and blocks dopamine. Sounds perfect, right? But a 2022 Cochrane review of three small trials found it didn’t reduce nausea or vomiting when given before opioids. Worse, it can cause muscle spasms, restlessness, and even tardive dyskinesia with long-term use. It’s not worth the risk unless nausea is clearly due to slow digestion.

Droperidol is another dopamine blocker. It works fast, but it’s got the same black box warning as ondansetron. The FDA has flagged it for causing life-threatening heart rhythm changes. Most hospitals avoid it unless there’s no other option.

Scopolamine and meclizine are better for dizziness-related nausea. If the patient feels like the room is spinning-especially when moving-they’re likely reacting to vestibular stimulation. These drugs target that specifically and don’t affect heart rhythm. But they cause drowsiness and dry mouth. Not ideal for someone who needs to stay alert.

What Doesn’t Work (And Why)

A lot of providers still give metoclopramide “just in case.” But the evidence says otherwise. The 2022 Cochrane review looked at three studies involving IV opioids like morphine and tramadol. None showed metoclopramide prevented nausea or vomiting. Not even a little. And no increase in side effects either-meaning it’s useless, not harmful. But it’s still used because it’s cheap and familiar.Prophylactic antiemetics-giving them before symptoms start-are not recommended for most patients. Why? Because OINV usually fades within a week. Giving a drug with cardiac risks or sedative effects for a problem that resolves on its own is like giving antibiotics for a cold.

There’s one exception: patients who’ve had severe OINV before, or those on high-dose opioids for chronic pain. For them, a short course of a safe antiemetic might help them stick with treatment.

Best Practices: What to Do Instead

The best way to handle opioid-induced nausea isn’t with a pill-it’s with strategy.- Start low, go slow. A low initial dose cuts nausea risk dramatically. For example, morphine at 1 mg twice daily for COPD-related breathlessness causes far fewer side effects than higher doses. Slow titration lets your body adjust.

- Rotate opioids. Not all opioids cause nausea the same way. Oxymorphone is 60 times more likely to cause nausea per milligram than oxycodone. Tapentadol is much gentler than both. If a patient gets sick on one opioid, switching to another often helps-without changing pain control.

- Use antiemetics only when needed. Don’t prescribe them preemptively. Wait until nausea appears. Then pick the drug based on the symptoms: dizziness? Try scopolamine. Gut slowdown? Try a low dose of metoclopramide. Vomiting with no dizziness? Ondansetron or palonosetron, but check heart history first.

- Monitor for serotonin syndrome. Opioids like tramadol, fentanyl, and methadone can interact with antidepressants (SSRIs, SNRIs) and migraine drugs (triptans). This combo can cause high fever, confusion, muscle rigidity, and even death. Always check the full med list before starting opioids.

- Teach patients what to expect. The CDC’s 2022 guidelines say providers must tell patients about nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, and constipation before starting opioids. Most patients don’t know this is normal-and temporary. When they’re warned, they’re more likely to stick with treatment.

When to Avoid Antiemetics Altogether

Some patients should never get certain antiemetics. Avoid ondansetron, droperidol, and palonosetron if the patient:- Has a history of long QT syndrome

- Takes other drugs that prolong QT (like certain antibiotics, antifungals, or antipsychotics)

- Has kidney or liver disease (slows drug clearance)

- Is elderly (higher sensitivity to side effects)

For these people, non-drug options are safer. Ginger supplements (1 gram daily) have shown modest benefit in some studies. Acupressure wristbands (like Sea-Bands) help some patients with dizziness-related nausea. And hydration-small sips of water or ice chips-can reduce vomiting episodes.

The Bigger Picture: Opioids Aren’t Forever

The goal isn’t to make opioids tolerable forever. It’s to use them only as long as needed. The CDC and FDA both stress that opioids are meant for short-term use-after surgery, injury, or acute flare-ups. For chronic pain, non-opioid options (physical therapy, NSAIDs, nerve blocks) are safer and more effective long-term.When opioids are necessary, the focus should be on minimizing harm. That means avoiding blanket antiemetic prescriptions. It means choosing opioids with lower nausea risk. It means educating patients so they don’t quit because they’re scared of being sick.

The real win? When a patient gets pain relief without vomiting. When they can sleep. When they can get out of bed. That’s not luck. That’s smart prescribing.

What to Do If Nausea Doesn’t Go Away

If nausea lasts longer than 7-10 days despite a stable opioid dose, it’s not OINV anymore. Something else is going on:- Is the patient constipated? That can cause nausea too. Treat the constipation first.

- Are they on other meds? Check for drug interactions.

- Do they have an infection, liver issue, or brain condition? Nausea can be a sign of something serious.

Don’t just crank up the antiemetic. Look for the real cause. Sometimes, reducing the opioid dose-even slightly-helps more than adding another drug.

Can I take ondansetron with opioids safely?

Ondansetron can be used with opioids if the patient has no heart rhythm problems and isn’t taking other QT-prolonging drugs. But it’s not first-line. Use it only if nausea is severe and other options won’t work. Always check the patient’s ECG history and kidney function before prescribing.

Why is metoclopramide not recommended for opioid nausea?

Studies show metoclopramide doesn’t prevent or reduce opioid-induced nausea or vomiting. It’s been tested in multiple trials and consistently failed to help. It also carries risks like muscle spasms and movement disorders. Unless nausea is clearly from slow digestion, it’s not worth the risk.

How long does opioid nausea last?

For most people, nausea and vomiting fade within 3 to 7 days of starting a stable opioid dose. The body builds tolerance. If symptoms last longer, look for other causes like constipation, drug interactions, or unrelated medical issues.

Which opioid causes the least nausea?

Tapentadol causes significantly less nausea than oxycodone or oxymorphone-about 3 to 4 times less per milligram. Morphine and hydrocodone are also relatively gentler. Oxymorphone is the worst offender. Switching opioids is often more effective than adding antiemetics.

Can antiemetics make opioid side effects worse?

Yes. Some antiemetics, especially those that cause drowsiness (like promethazine or scopolamine), can increase sedation and respiratory depression when combined with opioids. This raises the risk of overdose. Always consider the total sedative load. Avoid combining multiple CNS depressants unless absolutely necessary.

If you’re managing opioids for pain, remember: nausea isn’t a side effect to be masked-it’s a signal. It tells you the body is struggling. The best response isn’t always more drugs. Sometimes, it’s less opioid, a better choice, or just more time.

Shannon Amos

November 27, 2025 AT 08:00So let me get this straight-we’re giving people drugs that make them feel like they’re gonna hurl, then handing them another drug that might give them a heart attack to fix it? And we’re surprised people quit?

Classic medicine. Fix the symptom, ignore the system.

stephen riyo

November 27, 2025 AT 19:45Wait-wait-wait. I just need to say this: I’ve seen this so many times. Patients get on morphine, get nauseous, get prescribed Zofran, then end up in the ER because their QT’s stretched like taffy. And the docs? They just shrug and say, ‘Oh, we didn’t know.’

But you DID know. You read the black box warning. You just didn’t care enough to check their ECG history. And now? They’re dead. Or worse-alive but with permanent arrhythmias.

It’s not negligence. It’s laziness. And it’s killing people.

Wendy Edwards

November 29, 2025 AT 10:51Y’all are overcomplicating this. My grandma got on oxycodone after hip surgery-puked for two days, then just… stopped. No meds. No drama. Just… got used to it.

And guess what? She didn’t die. She watched her favorite soap operas and ate ice cream.

Maybe we just need to chill and let bodies adjust instead of throwing pills at every sneeze.

Also-ginger tea. Works better than half the stuff on this list. And it doesn’t cost $200.

Jaspreet Kaur

December 1, 2025 AT 06:49What if the real problem isn’t the opioid or the antiemetic but our addiction to control

We want to fix everything immediately so we don’t have to sit with discomfort

But nausea is not an enemy to be silenced it is a messenger

It says your body is adjusting your system is learning

Instead of reaching for the next pill we should be holding space for the process

And maybe that’s the most radical thing we can do anymore

Let it be uncomfortable let it be human

Albert Guasch

December 1, 2025 AT 20:57Based on the evidence presented in this comprehensive review, it is unequivocally recommended that prophylactic administration of antiemetics in opioid-naïve patients be avoided, given the lack of demonstrated efficacy and the potential for iatrogenic harm, particularly in the context of QT prolongation and central nervous system depression.

Adherence to the CDC’s 2022 guidelines regarding patient education and opioid rotation protocols represents the current standard of care and should be implemented universally in clinical practice.

Stephanie Deschenes

December 3, 2025 AT 12:18This is one of the clearest, most practical summaries I’ve read on this topic.

Thank you for emphasizing that nausea isn’t just a side effect-it’s a signal. Too many of us rush to suppress it without asking why it’s there.

Also, ginger and acupressure bands? I’ve seen patients respond better to those than to Zofran. And they don’t need a cardiologist on speed dial.

Keep sharing this kind of stuff. It saves lives.

Bea Rose

December 4, 2025 AT 02:54Metoclopramide doesn’t work. Ondansetron kills. Scopolamine makes you a zombie. Ginger is a placebo. So what’s left?

Nothing.

Just don’t use opioids.

Michael Collier

December 5, 2025 AT 18:50While the clinical recommendations outlined in this post are both evidence-based and clinically prudent, it is imperative that healthcare institutions institutionalize these practices through standardized protocols, electronic health record alerts, and mandatory provider education modules.

Without systemic change, individual clinician awareness remains insufficient to mitigate population-level harm.

Gina Banh

December 6, 2025 AT 13:54They keep prescribing Zofran like it’s candy. Meanwhile, the patient’s ECG is screaming and no one’s listening.

And don’t even get me started on how hospitals still use droperidol like it’s 1998.

It’s not ignorance. It’s institutional laziness.

Also-tapentadol is the real MVP. Why isn’t it the first-line opioid? Because it’s not cheap. And profit beats safety. Again.

Deirdre Wilson

December 8, 2025 AT 08:04So opioids mess with your brain’s ‘I think I’m poisoned’ button and your gut’s ‘I’m on vacation’ mode?

That’s wild.

It’s like your body’s running a horror movie while your pain’s trying to nap.

And instead of turning off the movie, we hand you a drug that might crash the whole system.

Why not just dim the lights and wait for the movie to end?

Also-ginger is basically magic. I’d rather chew a piece of it than take a pill that could stop my heart.

Damon Stangherlin

December 9, 2025 AT 16:41Just wanted to say I read this whole thing and it actually helped me talk to my dad about his pain meds. He was on Zofran for weeks and didn’t know it could hurt his heart. I showed him this and he switched to tapentadol. No more puking. No more scary ECGs.

Thanks for writing this. I think it’s gonna save someone’s life. Maybe mine too.

Ryan C

December 10, 2025 AT 02:24FACT CHECK: Ondansetron’s QT prolongation risk is dose-dependent and clinically significant at >16mg/day. Palonosetron has a longer half-life (40h vs 8h) but similar cardiac risk profile. Metoclopramide’s risk of tardive dyskinesia is 0.1-0.2% per year-low but irreversible. Tapentadol has 3.4x lower incidence of nausea vs oxycodone (J Pain 2015).

Also, ginger’s efficacy is borderline statistically significant in meta-analyses (p=0.047). Not a miracle. Just… slightly better than placebo.

And yes, I’ve read the Cochrane review. Twice.

Dan Rua

December 10, 2025 AT 06:53Man, I wish I’d read this before I gave my mom Zofran. She’s 72, on morphine for cancer pain, and had a scary episode last month.

Now we’re using scopolamine patches when she gets dizzy, and we’re slowly switching her to tapentadol.

She’s sleeping through the night for the first time in months.

Thank you for this. Seriously.

Mqondisi Gumede

December 10, 2025 AT 12:03You Americans think you own medicine

Every problem needs a pill

Why not just tell people to stop being weak

My people in South Africa take morphine with tea and no drama

You overmedicate everything

And now you want to ban droperidol because you're scared of your own shadow

Real men don't need Zofran

Douglas Fisher

December 12, 2025 AT 08:31This is so important.

I’ve been a nurse for 22 years, and I’ve seen so many patients quit opioids because they thought vomiting meant they were “addicted” or “doing it wrong.”

And then they’re in agony because they didn’t know nausea fades.

Thank you for saying this clearly. I’m printing this out for my unit tomorrow.

And yes-ginger tea. Always start with ginger tea.