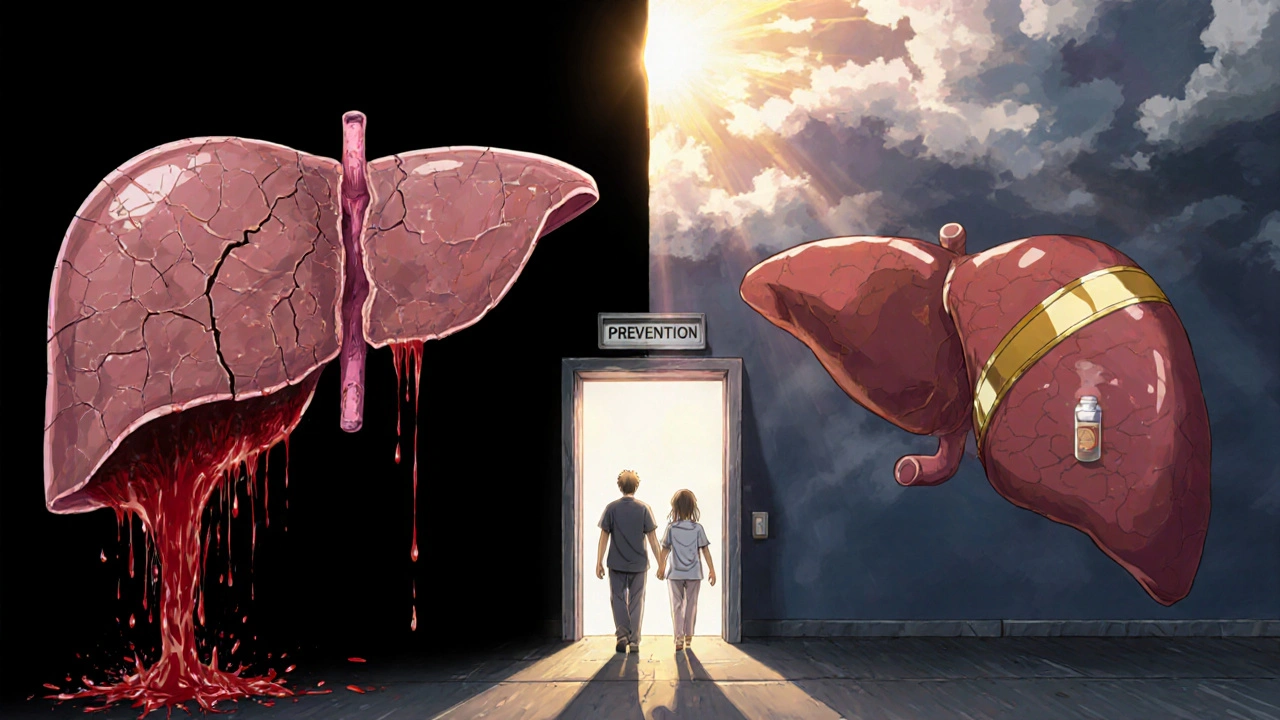

When your liver is damaged by cirrhosis, pressure builds up in the portal vein - the main blood vessel carrying blood from your intestines to your liver. This pressure forces blood to find new paths, creating swollen, fragile veins in your esophagus or stomach. These are called varices. And when they burst, it’s not just a medical emergency - it’s often deadly. About 1 in 5 people who bleed from varices die within six weeks. But here’s the good news: we know how to stop it. With the right combination of banding, beta-blockers, and smart prevention, many of these bleeds can be prevented - or controlled before they kill.

What Happens When Varices Bleed?

Variceal bleeding doesn’t come with warning signs. One moment you feel fine; the next, you’re vomiting bright red blood or passing black, tarry stools. It happens because the walls of these enlarged veins become paper-thin from constant pressure. The moment they rupture, blood floods into your digestive tract. Without quick action, you can lose liters of blood in minutes.

This isn’t random. It’s the result of long-term liver damage - usually from alcohol, hepatitis, or fatty liver disease. When the liver scars, it blocks blood flow. The body tries to compensate by creating collateral veins. But these veins aren’t built for high pressure. They bulge, stretch, and eventually break. That’s why managing portal hypertension isn’t optional - it’s life-or-death.

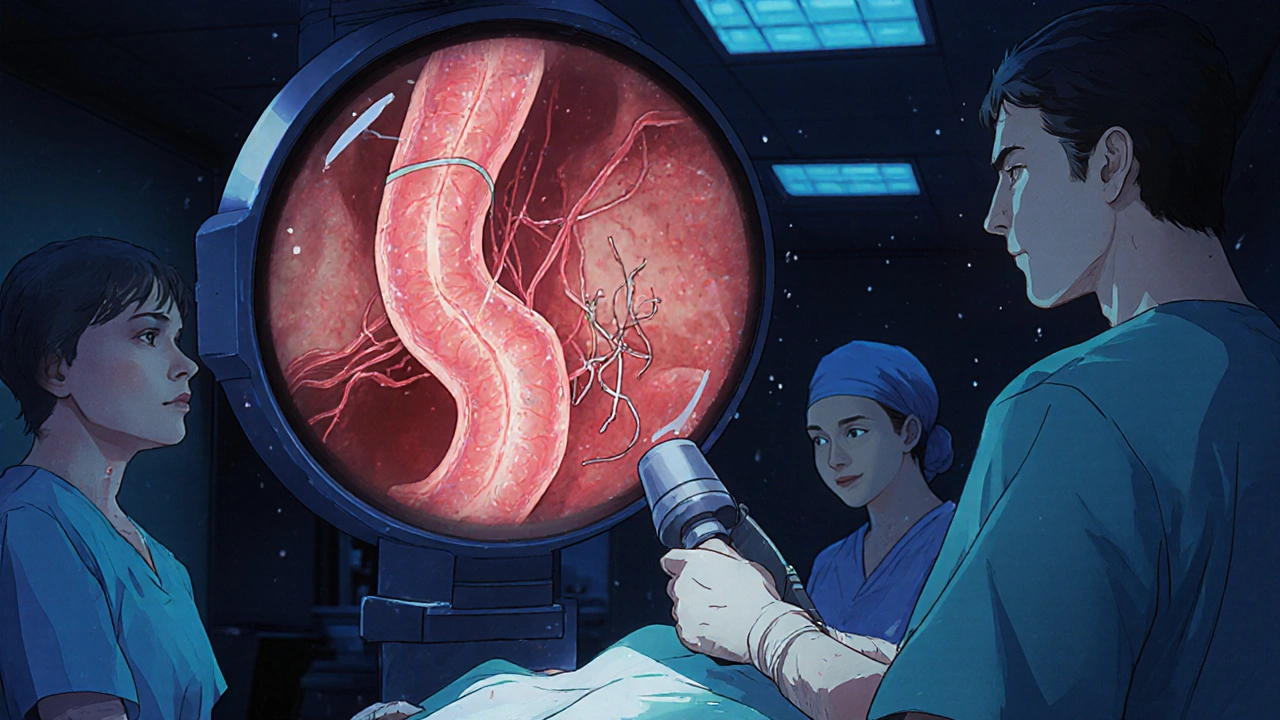

Endoscopic Band Ligation: The Gold Standard for Stopping Bleeding

If you’re bleeding right now, time is your enemy. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases says endoscopic band ligation (EBL) must be done within 12 hours of arrival. Delay it, and your chances of survival drop fast.

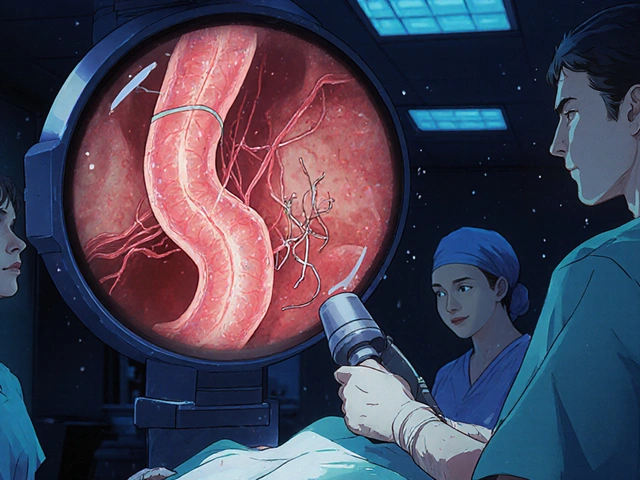

Here’s how it works: A doctor uses a thin tube with a camera (an endoscope) to find the bleeding varices. Then, using a special device, they place tiny rubber bands around the base of each swollen vein. The bands cut off blood flow. The varix shrinks, dies, and eventually falls off. Within weeks, the vein disappears.

This isn’t theory - it’s proven. Studies show EBL stops active bleeding in 90-95% of cases. That’s far better than older methods like sclerotherapy, which injected chemicals into the veins and caused more complications like strictures and infections. Modern multi-band devices, like the Boston Scientific Six-Shot system, let doctors treat multiple veins in one pass, cutting procedure time by 35%.

But it’s not perfect. In about 1 in 10 cases, the bleeding is too heavy for the endoscope to get a clear view. Or the patient is too unstable. That’s when other tools - like balloon tamponade or TIPS - become necessary.

Most patients need 3 to 4 banding sessions, spaced 1 to 2 weeks apart, to fully eliminate the varices. Each session costs between $1,200 and $1,800 in the U.S. But compared to the cost of ICU care after a rebleed? It’s a bargain.

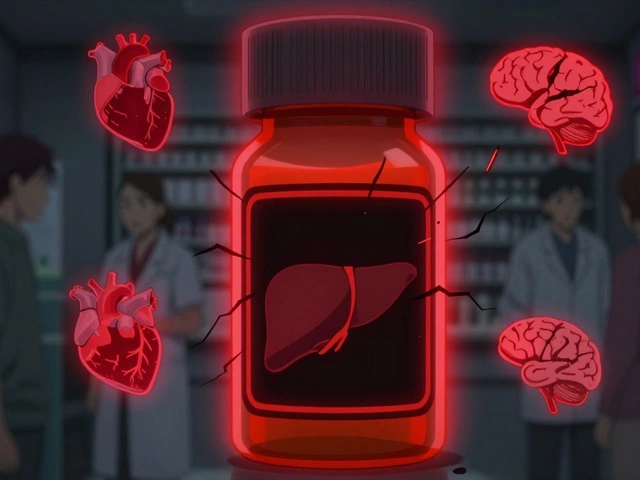

Beta-Blockers: The Silent Shield Against Future Bleeds

Stopping the bleeding once is only half the battle. Without treatment, more than half of patients bleed again within a year. That’s where beta-blockers come in.

Two drugs are used most often: propranolol and carvedilol. Both are non-selective beta-blockers. They don’t just slow your heart - they reduce blood flow to the liver, lowering the pressure in the portal vein. The goal? Cut the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) by at least 20%, or bring it below 12 mmHg. That’s the magic number that dramatically lowers rebleeding risk.

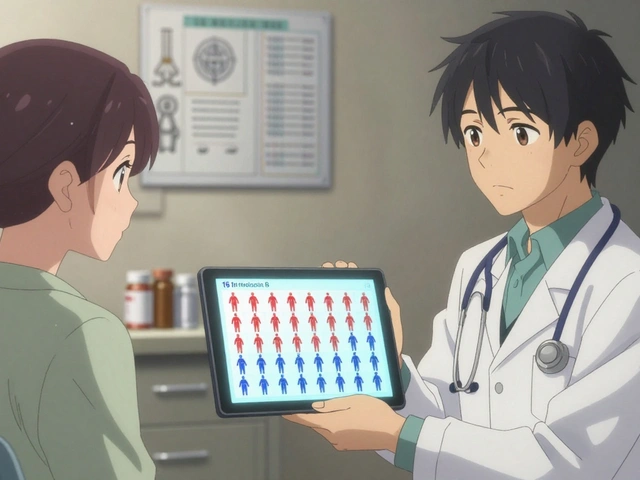

Carvedilol has an edge. In a 2021 trial of 287 patients, it lowered portal pressure by 22%, compared to 15% with propranolol. And both cut rebleeding risk by about half compared to no treatment. That’s why experts now say carvedilol could be the best first choice for primary prevention - especially in patients with large varices who haven’t bled yet.

But here’s the catch: these drugs aren’t easy to take. Side effects are common - fatigue, dizziness, low heart rate. About 1 in 3 people can’t tolerate the full dose. One patient on Reddit said propranolol left him so tired he couldn’t get out of bed. He switched to carvedilol, which worked better - but cost him $35 a month in copays.

Propranolol is cheap - $4 to $10 a month. Carvedilol? $25 to $40. Insurance helps, but not everyone can afford it. And if you have asthma, heart failure, or a very slow heart rate, you can’t take them at all.

Here’s what’s critical: beta-blockers alone won’t stop an active bleed. That’s why guidelines say they must be used with banding - not instead of it - after a first bleed. Alone, they only stop bleeding in 50-60% of cases. Together with banding? That jumps to over 90%.

When Banding Isn’t Enough: Other Options

Not all varices are the same. Esophageal varices respond well to banding. Gastric varices? Not so much. For those, doctors use balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO). A 2023 analysis of over 7,000 patients showed 30-day mortality was 6.2% with banding alone, but dropped to 2.8% when BRTO was added.

Then there’s TIPS - transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. This is a procedure where a metal mesh tube is placed inside the liver to create a new channel for blood to bypass the blocked area. It’s powerful. In high-risk patients (Child-Pugh B or C), TIPS cuts 1-year mortality from 39% to 14%. But it comes with a big trade-off: up to 30% of patients develop hepatic encephalopathy - brain fog, confusion, even coma - because toxins that should be filtered by the liver now enter the bloodstream directly.

TIPS isn’t available everywhere. Only 45% of U.S. hospitals have interventional radiologists who can do it within 24 hours. That’s why some experts push for early TIPS - within 72 hours - for high-risk patients. Others warn it’s overkill if you don’t have the right team.

For now, TIPS is reserved for patients who keep rebleeding despite banding and beta-blockers. Or those with severe liver damage who aren’t candidates for transplant.

Prevention: The Most Important Step

The best way to avoid variceal bleeding? Don’t let it happen in the first place.

If you have cirrhosis, you should be screened for varices. An endoscopy every 2-3 years (or sooner if you have large varices) is standard. If you have medium or large varices and haven’t bled yet, you should be on a beta-blocker - even if you feel fine. Carvedilol is now the preferred choice for primary prevention, especially if you can tolerate it.

But prevention isn’t just drugs. It’s avoiding alcohol completely. It’s managing your weight if you have fatty liver. It’s getting vaccinated for hepatitis B and C. It’s taking your medications as prescribed. And it’s knowing the warning signs: black stools, vomiting blood, sudden dizziness. If you notice any of these, go to the ER - don’t wait.

And don’t underestimate the power of support. One patient on a liver forum said, “I dread the banding appointments every two weeks - but I know it’s saving my life.” That mindset matters. You’re not just treating a vein. You’re protecting your future.

What’s Next? New Treatments on the Horizon

The field is moving fast. In 2023, the FDA approved a long-acting version of octreotide - Sandostatin LAR - that only needs monthly injections instead of daily. That could help patients who struggle with adherence. Right now, only 62% take their meds as prescribed.

Researchers are also testing artificial intelligence to predict who’s most likely to bleed. By analyzing liver scans, lab values, and even voice patterns, AI might one day spot danger before it happens.

And the PORTAS trial is exploring a new way to do TIPS - using a needle through the spleen instead of the neck. If it works, it could make TIPS available in 75% of U.S. hospitals instead of just 45%.

But none of this matters if access is unequal. Uninsured patients die from variceal bleeding at a rate 35% higher than those with insurance. That’s not a medical problem - it’s a system failure.

What You Need to Remember

Variceal bleeding is scary. But it’s not inevitable. Here’s what you need to do:

- If you have cirrhosis, get screened for varices - don’t wait for symptoms.

- If you have large varices, start a beta-blocker. Carvedilol is often better than propranolol.

- If you’ve bled before, banding is your first-line treatment. Do it within 12 hours.

- Take your beta-blockers every day, even if you feel fine. Missing doses increases rebleeding risk.

- If you can’t tolerate beta-blockers, talk to your doctor about alternatives - don’t quit.

- Know the signs of bleeding. If you see red blood or black stools, go to the ER immediately.

Surviving a variceal bleed isn’t luck. It’s science. And with the right tools - banding, beta-blockers, and prevention - you can live longer, healthier, and with far less fear.

Can beta-blockers stop a variceal bleed once it’s started?

No. Beta-blockers are for prevention - not emergency control. Once bleeding starts, you need endoscopic band ligation within 12 hours. Beta-blockers help reduce pressure afterward to prevent rebleeding, but they won’t stop active bleeding on their own.

Is endoscopic banding painful?

The procedure itself is done under sedation, so you won’t feel it. Afterward, some people have sore throat, chest discomfort, or mild swallowing pain for up to two weeks. That’s normal. Severe pain, fever, or vomiting blood after banding means you need to call your doctor right away - it could mean another bleed.

Can I stop taking beta-blockers if I feel fine?

Absolutely not. Even if you feel perfectly healthy, stopping beta-blockers can cause portal pressure to spike again. Rebleeding risk jumps by 50% or more within weeks. These drugs work silently - you won’t feel them working, but they’re protecting you. Never stop without talking to your hepatologist.

Why is carvedilol better than propranolol for varices?

Carvedilol lowers portal pressure more effectively - by about 22% compared to 15% with propranolol. It also has additional effects on blood vessels that help reduce pressure in the liver. Studies show it reduces rebleeding risk just as well as propranolol, but with greater pressure control. For many patients, it’s the preferred choice for both primary and secondary prevention.

How often do I need endoscopic banding?

Most patients need 3 to 4 sessions, spaced 1 to 2 weeks apart, to completely remove all varices. After that, you’ll need follow-up endoscopies every 6 to 12 months to check for new varices or recurrence. Even after eradication, you still need to stay on beta-blockers unless your doctor says otherwise.

Variceal bleeding is a serious condition, but it’s not a death sentence. With timely treatment, consistent medication, and smart prevention, many people live for years - even decades - after their first bleed. The key is acting early, staying consistent, and never giving up on your care.

Andrew Camacho

November 22, 2025 AT 17:22Man, I had a buddy go through this last year - got dumped with cirrhosis after 15 years of ‘just a few beers’ and now he’s on carvedilol, banding every two weeks, and crying in the parking lot after his third session. But here’s the kicker - he’s still alive. That’s more than I can say for half the guys at the bar who think ‘liver disease’ is just a buzzword. Stop drinking. Get screened. Don’t be a statistic.

Arup Kuri

November 24, 2025 AT 16:37beta blockers are just a big pharma scam to keep you hooked on pills while they sell you more liver scans. i seen a guy in delhi who cured his cirrhosis with neem leaves and yoga. no drugs no banding just pure indian wisdom. the system wants you dependent. dont fall for it. they dont want you healthy they want you paying.

Elise Lakey

November 26, 2025 AT 06:02I’ve been reading this whole thing and I’m just wondering - what’s the long-term quality of life like for people who’ve had multiple banding sessions? I know survival rates are good, but what does daily life actually feel like? Is the fatigue from carvedilol manageable? Are people able to work, travel, or just… live normally after a few years?

Erika Hunt

November 27, 2025 AT 21:51I just want to say how deeply moved I am by the sheer humanity in this post - the way it doesn’t just list facts, but acknowledges the emotional weight of living with this condition. The patient who dreads banding appointments but keeps showing up? That’s courage. The one who can’t afford carvedilol and still takes it anyway? That’s dignity. And the fact that we’re even talking about access disparities? That’s progress. This isn’t just medicine - it’s a mirror of our society, and it’s heartbreaking and beautiful all at once.

Sharley Agarwal

November 29, 2025 AT 15:33Propranolol is cheap because it’s old. Carvedilol is expensive because they made it to exploit people. You think this is medicine? It’s capitalism with a stethoscope.

prasad gaude

December 1, 2025 AT 14:24In India, we say ‘jhatka’ - a quick blow to end suffering. But here, we band, we block, we beta, we wait. Is this healing or just delaying the inevitable? My uncle had cirrhosis - he drank, he suffered, he died. We did everything right - screening, pills, diet - and still, the liver won. Maybe we’re fighting the wrong war. Maybe the soul needs peace more than pressure gradients.

Srikanth BH

December 1, 2025 AT 18:39Hey, if you’re reading this and you’ve got cirrhosis - I see you. I know it’s hard. The meds make you tired. The appointments feel endless. But you’re not weak for needing help. You’re strong for showing up every day. One banding session, one pill, one day at a time - that’s how you win. You’ve got this.

Jennifer Griffith

December 2, 2025 AT 09:11wait so carvedilol is better than propranolol? i thought they were the same thing?? like why do they even make both if one’s just a fancy version?? and why does it cost 10x?? also i think they misspelled ‘hepatic’ somewhere

Roscoe Howard

December 3, 2025 AT 14:28It is an undeniable fact that the American healthcare system, in its current iteration, is fundamentally incompatible with the preservation of human life. The fact that a life-saving procedure such as endoscopic band ligation is subject to insurance approval, geographic availability, and socioeconomic status is not merely a flaw - it is a moral abomination. The United States of America, a nation that spends more per capita on healthcare than any other on Earth, permits its citizens to die from preventable hemorrhage. This is not medicine. This is negligence dressed in white coats.

Andrew Camacho

December 4, 2025 AT 23:21@Roscoe Howard - you’re not wrong, but let’s be real: the guy who can’t afford carvedilol isn’t sitting in a Senate hearing. He’s choosing between his meds and his kid’s school lunch. You wanna fix the system? Start by making the drugs cheap. Not just talk about ‘moral abominations.’ I’ve seen people die because their copay was $40. That’s the real horror story.